Range plants respond with vigor following post-fire rehabilitation efforts by the BLM, Forest Service

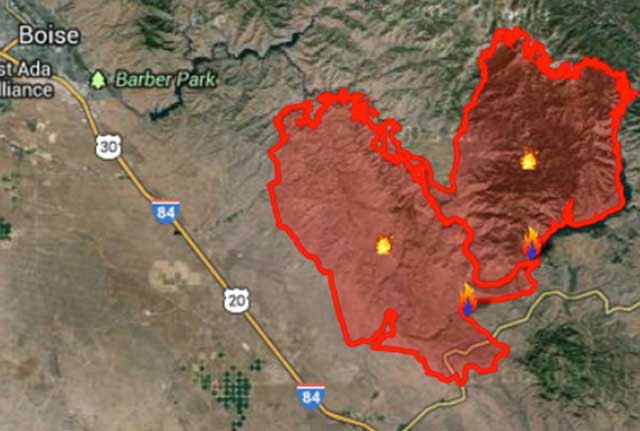

The Pony and Elk complex wildfires near Mountain Home had a big impact on the landscape, wildlife, cabin owners, ranchers and recreationists. Touched off by lightning in 100-degree heat, the fires consumed 280,000 acres of rangelands and forests in a matter of days, racing from Black’s Creek to Featherville. The blazes also charred 38 homes and 43 outbuildings near Pine and Fall Creek.

Rancher Charlie Lyons checks out the range plants and robust willow growth in the Dixie Creek area in the summer of 2014, one year after the Elk and Pony complex fires burned 280,000 acres of BLM and Forest Service land.

Immediately after the blazes were contained, federal authorities closed access to fishing and camping along the popular South Fork of the Boise River, shut down 150 miles of ATV trails in the Danksins, and more than 20 ranchers with summer range on BLM and Forest Service lands had to remove their cattle from the burn zone for at least two years to allow the land to heal.

In the fall, federal agencies took quick action to stabilize the soil and restore plant communities, a proactive step to jump-start nature’s own recovery. Federal officials explained the highest priorities in crafting an emergency-response strategy.

“Right after the fire, it’s human life and safety, just like fire suppression,” says Cindy Fritz, natural resources specialist for the Bureau of Land Management. “Second is soil stabilization. Are hillsides intact? Will they remain intact? If we have an event out here, are we going to have soil loss? The third is threatened and endangered species. Up here, it was the sage grouse habitat.”

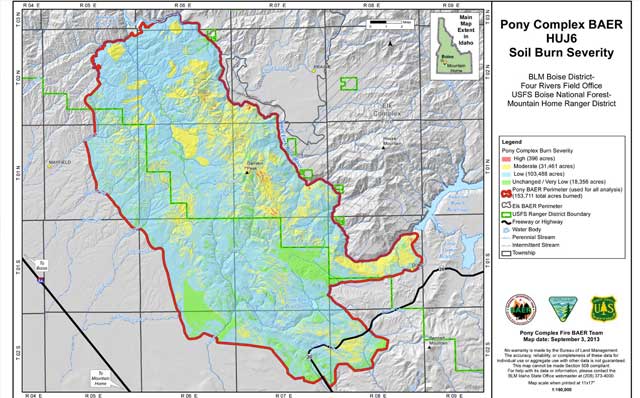

“We were looking at the moderate to high soil burn severity in the upper parts of the watershed, what we call flood- source areas,” adds Terry Hardy, Forest Burned Area Emergency Response (BAER) Coordinator for the Boise National Forest. “We can’t really treat all of the area, so we have to focus on areas where we have values at risk.”

Those areas included campgrounds, roads and culverts, and the upper watershed in the Boise National Forest.

Even though the fire burned hot, the actual soil burn severity was low to moderate on BLM lands, and high to moderate on Forest Service lands. The loss of shrub cover on BLM lands was significant; 44,000 acres of priority sage grouse habitat burned in the fires.

Before the rehab work could begin, BLM and Boise National Forest officials crafted a rehabilitation plan. They did so via a group of experts, called the Burned Area Emergency Response team, or “BAER” team for short.

Fire perimeter areas of the Pony and Elk complex fires.

The fire-rehab plans called for aerial seeding and drill-seeding to stabilize the soil and restore plant communities, hand-planting of sagebrush and bitterbrush for sage grouse habitat and winter big game range, tree-planting and more.

After submitting the BAER plans to agency budget officials in Washington D.C., the BLM received authorization to spend $1.9 million on fire rehab, and the Boise National Forest was authorized to spend $4.5 million.

Full funding was critical to get a quick start on the rehab work, but several wrinkles occurred:

- Over 3 inches of rain fell in one night in September, causing a number of creek blowouts and washing tons of debris into the South Fork of the Boise River, a blue-ribbon trout fishery.

- Congress reached a budget impasse in October, shutting down for 16 days. That caused a delay in rehab projects and furloughed federal employees.

“We were delayed with the furlough in just about every aspect of the project,” Hardy said.

The soil burn severity in the Pony Complex fire on BLM and Forest Service land was primarily low to moderate, and on the Elk Complex fire, the soil burn severity was more severe on Forest Service lands.

Above, BLM John Deere tractors pull drill-seeding implements in

“triples” to cover as much as 100 acres in one day. Right, choppers drop seed mixes onto the fire zone to jump start nature’s recovery.

The creek washouts changed several rapids in the South Fork of the Boise River, getting the immediate attention of anglers and rafters who use it frequently. Trout-fishing groups rallied 100 volunteers to plant trees and shrubs along the South Fork to help with recovery efforts.

Once the government furlough ended, Forest Service and BLM emergency response teams marshalled their crews and got to work in the short window of time that remained before winter. BLM drill-seeding crews went to work in the hills north of Mountain Home in late November, planting about 3,500 acres.

“We did this all in-house,” Fritz says. “We will pull, we call them triples – they’re 14 feet wide, so you can hook them up in a triple, to get a 45-foot wide swath. And you can hit 100 acres a day with one of those.”

The BLM dropped an aerial seed mix on 32,800 acres of the Pony complex fire zone, or 80 percent of the burn area. The seed mix included native grasses, alfalfa and sagebrush.

The Forest Service seeded about 2,000 acres in the headwaters of the mountains affected by the Elk complex fire. They used a fast-growing wheat seed called triticali. And then they covered the seeding areas with straw mulch via helicopter.

“Triticali. It’s a sterile wheat mix, so it’s non-persistent,” Hardy explains. “It will grow, it dies off, it produces organics, provides stability and soil moisture.”

The Forest Service also seeded about 700 acres of sage grouse habitat in the Elk Complex fire zone with a mix of triticali, wheatgrass, squirrel tail and sagebrush. As for hand-planting efforts, several hundred Idaho Fish and Game volunteers have planted thousands of sagebrush and bitterbrush seedlings in several locations in the Pony and Elk fire zones. Plus, 800 forbs were planted near a sage grouse lek.

One year later, the Forest Service and BLM rehab efforts are showing positive results. Cindy Fritz checks on a drill-seeding next to the Cow Creek Road. “As you can see, we had a really good year,” she says. “We had favorable moisture, we had favorable temperatures, we’ve got really good soil here, so where we could drill seed, we had a really good take … but this is not reflective of what happens every year.”

Fritz also saw sagebrush seedlings coming up from the fire zone. “This is from our aerial seeding. That’s what we want to come back. This is for sage grouse. On a favorable year, aerial seeding is a good way to get sagebrush in the ground. Yeah, really like this site.”

Bitterbrush and sagebrush plants resprouted a year after the fires on their own, plus aerially seeded sagebrush plants also were seen sprouting in a number of locations in the fire zone. This is good news for wildlife.

Chad Gibson, a professional range scientist, checked on vegetation regrowth near a sage grouse lek on BLM land. Plants in this location were drill-seeded and aerial seeded. “The bluebunch is coming really thick,” Gibson says. “You can see the growth in lots of places. There are a lot of sagebrush seedlings coming, and over here, there’s quite a variety of forbs, the burnet came in really well, alfalfa is coming good, there’s a pretty good component of everything you’d want on a site.”

“It should look excellent next spring. This grass that has this kind of a start at this time of year is going to be pretty robust come spring.”

Forest Service officials are pleased with seeding results as well. “I’m confident in the seeding,” Hardy says. “I think they were pretty good from what I saw. You want a thin cover, about 70% cover. Don’t want a continuous matt. That can be detrimental to the seeds in the soil.”

In the Dixie Creek area near Anderson Ranch Road, Forest Service range technician Monte Miller checked on vegetation growth a year after the fires. “Out here in this meadow, or grassland type, things are recovering quite nicely,” Miller says. “In the black areas, where the hydrophobic soils exist, definitely have the concerns there because of the lack of ground cover. We do have some plants coming in from the seeding. We’ll see with the moisture this fall if they become established.”

One year and a half after the fires, BLM and Forest Service have been slowly opening access to the burn zones as resources allow. Campers, anglers and floaters can access the South Fork of the Boise River again. The Forest Service expects to reopen the popular Danskin OHV trails on Forest Service land in late May or early June.

Connie Tharp of the Natural Resources Conservation Service talks about how many seeds from the first year of growth following the fires were lying on the ground, and the hoof action of livestock, elk and deer are helpful in “planting” those seeds into the ground below the soil crust.

As for livestock grazing, the BLM is considering re-opening lands to grazing where post fire resource objectives have been met or plant composition is dominated by annual species. The Forest

Service expects to open some areas to grazing after seed ripe, where soil burn severity was low to moderate and site-specific monitoring shows that conditions are favorable. Twelve grazing allotments were affected by the fires on Forest Service land.

“We’d like to get grazing back here as soon as we can, but not at the detriment of the resource,” Miller explains. “What I can tell you is that it will be on a case by case basis.”

A bluebunch wheatgrass plant was doing well in the fall of 2014, a year after the drill-seedings. But the roots of the plant were still in the development stage. (BLM photo)

Recreationsts can always go find another place to play, but for the 20 ranchers affected by the fires, the 2-year closure is a big hardship. Public lands grazing permits are an integral part of a ranching operation. Ranchers normally rely on the federal range for summer grazing. With the closures, they’ve had to scramble to find alternative grazing lands and cut their herds.

Because of the favorable wet weather and robust plant recovery in the last year, some ranchers would like the agencies to consider opening lands for livestock grazing when the plants are ready on a site-specific basis.

Range scientist Chad Gibson inspected some BLM lands in the burn zone last summer at the request of rancher Charlie Lyons to get an independent opinion. “What they’re talking about is whether it should be grazed again. And the evidence would indicate that it’s ready to graze now,” Gibson says. “You’ve got a huge amount of cover. You’ve got bulbus wheatgrass up here as well as poa, and if you want to keep that, it needs to be grazed to reduce the competition.”

If the slopes aren’t grazed, Gibson says, then the cheatgrass that grew in thick after the fire could completely take over the site.

Connie Tharp of the Natural Resources Conservation Service also checked on range conditions with Lyons. “When we’re evaluating a stand to determine if the plants are established, we’ll look at the density, the composition, the diversity and then we’ll do a simple pull test,” Tharp explains. “With that pull test, we’ll check to see if the plants are rooted down and established. What I’m seeing, in plant composition, is that the plants are well-established and rooted down. This range is ready.”

Lyons has been grazing his private lands while he waits for BLM and Forest Service lands to reopen for grazing. “I was interested to see how the impact comes back versus the federal range where they’ve taken us off the last two years,” Lyons says. “I think I’m going to outperform what they’re doing by coming in here and creating impact. And utilizing what forage is here. The hoof action is going to increase the number of seedlings I get in these bare areas that did burn hot.”

Rancher Charlie Lyons checks out some bitterbrush plants that were resprouting in the summer of 2014.

What Lyons means is that by grazing the land, the cows will help push seeds into the ground. Wildlife do that, too. Connie Tharp explains. “As the cattle or the elk or the deer — any of those — as they walk across the ground, as they move, and you’ll see the seed incorporated into the soil,” she says. “So when you get the right moisture on it, when the conditions are conducive, those seeds are going to germinate and become grass plants like the response we’re seeing. Yes, that will help with the recovery.”

Lyons also worries that if knee-high grasses aren’t grazed, the BLM lands will be prone to burn again. “I think for us not to utilize this in the spring, like we should have, or even next spring, start harvesting this forage, we’re going to have a real problem.”

Life on the Range will continue to track this story as it unfolds in the future.

Steve Stuebner is the writer and producer of Life on the Range, a public education project sponsored by the Idaho Rangeland Resource Commission.

© Idaho Rangeland Resources Commission, 2015