Emmett sheep rancher John Peterson is an eternal optimist.

He loves being a sheep rancher. He’s done it for 30 years and counting.

“I like being out here. I like working for myself,” Peterson says. “I taught school for 3 years, I poured concrete and did construction work as we worked into the sheep biz. You’re your own boss. I have to remind myself, going up to herder’s camps, be happy and be thankful. You could be in an office somewhere or still pouring concrete.”

Peterson’s wife, Anita, has Basque roots, a deep connection to the sheep industry.

“My wife and I grew up in Idaho as kids. Anywhere you went camping, you usually had to drive through bands of sheep,” he says. “I was always fascinated by it. Thought it’d be a fun way to make a living. Fun is not the right word probably, but it’s always been interesting, you know.”

Going into the 2020 grazing season, Peterson faced two new challenges. A major tussock moth outbreak on Packer John Mountain forced Peterson to reduce his sheep numbers.

The bug infestation led to salvage logging activities. By reducing his herd, he could zigzag around the logging activities and stay in business.

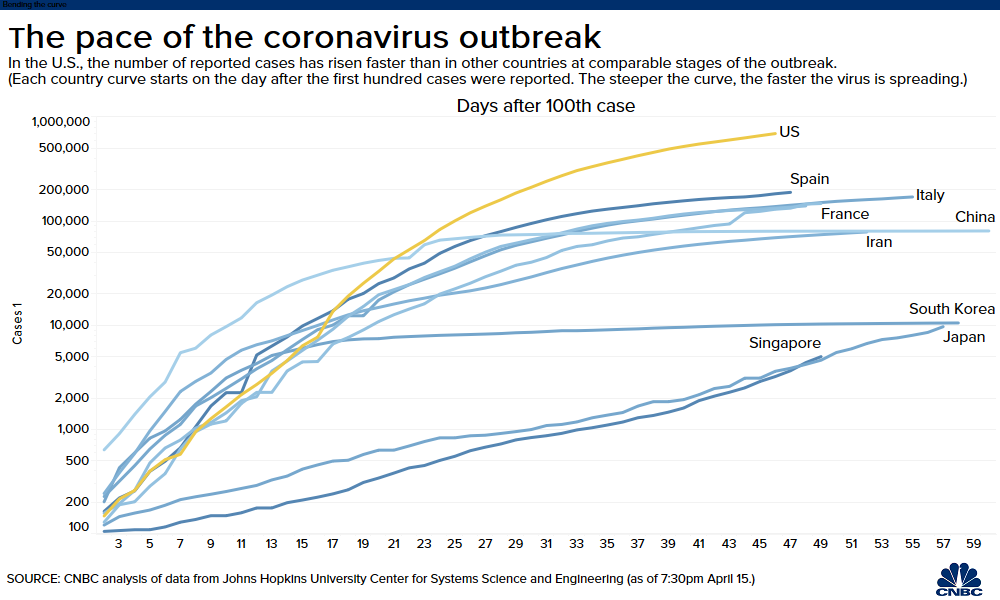

And then in March 2020, Peterson and sheep ranchers West-wide got caught in the cross-hairs of the Covid-19 pandemic. Suddenly lamb prices plummeted badly.

“When the pandemic hit, everything shut down,” says Sam Boyd, a marketing specialist with the Rocky Mountain Sheep Association. “Cruise lines and restaurants throughout the country shut down, and that’s where the majority of the lamb in this country is sold into and consumed.

“When the pandemic hit, everything shut down,” says Sam Boyd, a marketing specialist with the Rocky Mountain Sheep Association. “Cruise lines and restaurants throughout the country shut down, and that’s where the majority of the lamb in this country is sold into and consumed.

The cruise ship industry was a big buyer of lamb until the covid pandemic shut down the tours completely in 2020.

“It’s been quite a devastation. The prices have come down 40-45 percent from where they were, and it’s leading to some financial struggles for these producers.”

When Peterson shipped his sheep to market last fall, prices were bad. But within weeks, the market suddenly changed.

“We put them in a feedlot in California, and fed them, and it turned out good for us,” Peterson says. “The market improved and came back and strengthened substantially.”

This is the uncertain life of a modern-day sheep producer – they have to cope with many variables almost every day, every year. But Peterson is OK with that.

Newborn lambs are paint-branded along with the mother ewe to ensure they stay together when placed with larger groups.

Seeing a new crop of baby lambs being born in good weather conditions gets Peterson revved up.

“I think the lambs look real good. Real promising. So that’s good,” he says. “Yeah, I’m optimistic, it’s a lot more fun when there is optimism, you think boy, these lambs might be worth something this year. This year looks promising, real promising.”

The Life on the Range crew followed Peterson’s sheep flocks for a year – from lambing to shipping. Let’s follow along and learn what’s involved in raising quality lambs, following the green, from the low country to the high country of Idaho.

Lambing

Lambing begins in January at the Peterson Ranch. The ewes came into lambing season fat and jolly from grazing on alfalfa fields nearby.

“The ewes have lambed well. The ewes came in in good shape. They were on hay fields all fall, more than we could get to. That doesn’t happen every year,” Peterson says.

Small groups of ewes and lambs are placed in sun pens outside the lamb sheds to make room for newborns that need shelter.

In mid-January, the ewes begin giving birth to lambs. Peterson’s helpers quickly move the mother ewes into the lambing shed to keep the newborns out of the wind and cold.

“Every ewe comes in with her lambs,” he says. “We put them in these pens. They’re here for 2-3 days. The ewe goes out into these sun pens, the pens are mucked out, they’re re-bedded, and we’re ready for the next bunch.

“The guys are continually picking up ewes that have lambed. The weather’s been mild, so it’s not that crucial, but sometimes, you need to get them in right away.”

While the ewes and lambs are in the shed, they get a unique paint-brand number to keep the ewes and lambs together. “We like to keep them in here for as long as we can keep them in, they all do better,” he says.

And then, the ewes and lambs are moved outside.

One of Peterson’s livestock guardian dogs hangs out with ewes that have yet to give birth.

“They go out in the sun pens out here,” Peterson says. “We put together two ewes with twins or four ewes with singles, and it’s just a matter of mixing them in with larger bunches, until they end up in these pastures with groups of 250 ewes and lambs and that’s a truckload.”

Some ewes have twins; some have singles; but ultimately, they try to get two lambs paired up with each ewe through grafting. “We graft a lot of lambs,” he says. “Your feed costs are higher and your labor costs are higher when you shed-lamb, so you’ve got to try to get twins on every ewe you can.”

Spring Range at Avimor

In early April, the foothills above the Avimor Community begin to green up, and it’s time for Peterson to truck the sheep to a drop-off point on the edge of the subdivision.

Some Avimor residents come out to watch and take pictures.

Ewes and lambs unload on the edge of Avimor subdivision, north of Eagle

From this point forward, the sheep will follow the green-up on a Big Journey from Avimor to the Boise Ridge to Garden Valley to Smith’s Ferry. The grazing season will finish up in in late August, when the lambs are shipped to market.

The Big Journey is 65 miles by highway from point to point – but it’s at least twice that far going through the mountains.

Peterson’s herders are ready for the long journey, with face-masks to prevent the spread of Covid. They’ll be camping outdoors with the sheep for the next 6 months.

A number of livestock guardian dogs will tag along with the sheep as a non-lethal method of predator control. The dogs keep the coyotes at bay, and they also defend the sheep from mountain lions, black bears and wolves.

“The coyotes, they’ll nickel and dime you, they’ll try to take a lamb every night if they can, but they’re not a threat to kill in big numbers,” Peterson says. “Last year, we had wolves all around us on our summer range, and we had no confirmed kills, and that’s because we had the best combination of dogs that we’ve had.”

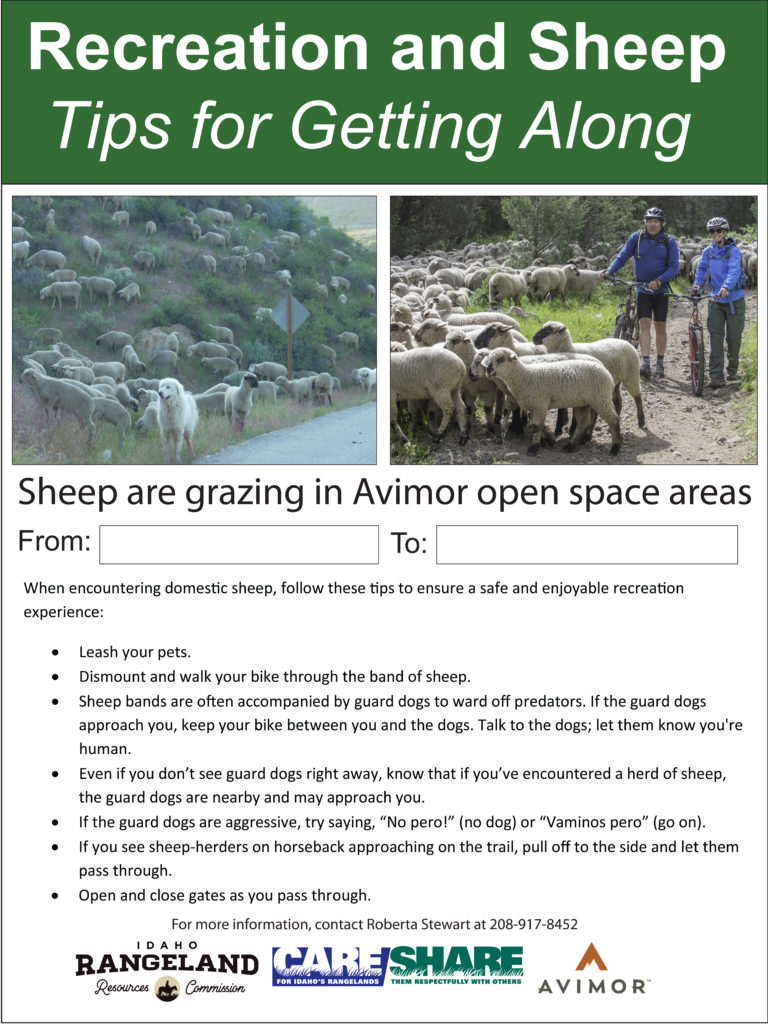

Guard dogs are very protective of the sheep, and that means they can be a bit testy around hikers and mountain bikers when the sheep are grazing around recreation trails.

Peterson has talked to Avimor residents about what to do.

When mountain bikers encounter sheep on the trail, it’s best to dismount and walk your bike through the sheep so as not to antagonize the guard dogs.

“We put out signs. We talked to people,” he says. “The white dogs, they’re protective of the sheep. Get off your bike. Talk to them. If you act like you’re running from them, they’ll think you’re prey. You stop and talk to them. Let them know you’re human.”

Walkers and joggers should leash their pets when sheep and guard dogs are in the area. Avimor has more than 20 miles of hiking and biking trails in the area, recreationists are co-existing with the sheep and guard dogs.

“The biggest part is education,” he says. “We make an effort to work with the people. They’re supportive of what we do. I keep my head down, and graze through there and no problems!”

“The biggest part is education,” he says. “We make an effort to work with the people. They’re supportive of what we do. I keep my head down, and graze through there and no problems!”

In late April, the sheep are bedded down in a grassy mountain bowl next to the Broken Horn Trail in Avimor. It’s quiet and the sheep are happy. The sheep herder’s camp is located on a hilltop nearby, with the pack stock grazing quietly beside the tent. Stack Rock, an iconic feature near Bogus Basin Ski Area, can be seen off in the distance.

Heading north on the Boise Ridge

As the green-up occurs in May, Peterson’s sheep move up on the Boise Ridge and graze slowly toward Harris Creek Summit and continue toward Garden Valley.

In the early summer of 2020, the weather stayed cool, wet and snowy almost into June.

Finally, spring gave way to summer and the ewes and lambs had tons of forage to eat on their way down the mountains into Garden Valley.

The sheep grazed in succulent green meadows in Garden Valley on a late June evening. Even the elk thought it was a perfect place to be.

The following morning, Peterson and his crew drove the sheep from the meadows to the little town of Crouch via the Banks to Lowman Highway.

Happy sheep graze in succulent meadows in Garden Valley the night before a sheep drive through the little town of Crouch the next morning.

They started at 6 a.m. to avoid disrupting vehicle traffic. And it all went smooth. The sheep passed through Crouch and then north on the Middle Fork Road.

Eventually, they steered the sheep into a private land meadow, where the animals could hang out and graze after the busy morning.

“I always worry when they’re on the highway,” Peterson says. “This morning went as good as it could. There was very little traffic, cool today, the sheep, they moved, nobody mad, nobody had to go anywhere in a hurry. 4.5 miles and started a little before 6, and now it’s 7:30.”

The sheep looked happy grazing in the tall-grass meadow and the lambs were doing well. The cool and wet June weather provided plenty of feed for the sheep.

“I don’t want jinx anything. But I think they look at little better. Seems like any year I think that, then I’m wrong. So I’m not going to say,” he says.

Peterson says landowners like him to graze his sheep around their homes to keep the fire danger down.

Trailing sheep through Crouch at 7 am before most people were awake made things go smooth.

“With all of the forage this spring, people that live with homes in the timber like this are concerned about fire. The cabin owners, they used to shoo us away, and now they ask the herders to come down and graze a little more time around their property.”

By this time, the Covid-19 pandemic had swept the world and lamb prices went south. Peterson was well-aware.

“The thing that matters now is what will the lambs be worth in the fall in the end of August, when they come to the corrals,” he says. “That’s the unknown this year. The way the market is now, it could be a $1.30 or $1.40, which is well below our break-even … ”

But Peterson is still optimistic.

Peterson’s sheep graze in a tall-grass meadow north of Crouch after the morning sheep drive.

“It’s been a good year; the lambs look good, and I think we’re supposed to get rain tomorrow. Some of the country up high might not be even ready yet.”

Now Peterson’s sheep will be moving north from toward Packer John Mountain, where the tussock moth outbreak occurred, and salvage logging activities were going full-bore during the summer of 2020. You could see dust rising from log truck traffic all over the mountain.

Summer Range – Packer John Mountain

About 13,000 acres of timber were affected by the tussock moth outbreak, and the Idaho Department of Lands plans to harvest about 6,400 acres of timber, mostly Douglas fir, to salvage their value.

IDL officials helped Peterson plan a safe route across Packer John Mountain for the sheep to pass through.

Western tussock moths

“John’s been really great to work with. I’ve worked with him over 10 years,” says Dean Johnson, Range Specialist for the Idaho Department of Lands. “It is going to be an effect on his operation because of the size of this outbreak. So we’ll work with him this fall, and continue to work with him the best we can so we can find other routes around the plantation and harvesting activities.”

Following the salvage logging, protecting the tree-plantations will be a big priority in the next couple of years, Johnson said.

“We’re going to plant about 1.4 M trees on these 6400 acres. We usually like to have a success ratio of 20-60%. Like to get 125 trees/acre,” he says.

“The concern is to keep the sheep from eating the tops of the trees or trample them. The sheep don’t normally like to eat the trees, but there’s so much grass and stuff around them that they could eat the tops of the trees or trample them, and that could ruin the plantation as well.”

So those will be concerns in future years. But in the summer of 2020, Peterson’s crew just had to herd the sheep around logging operations and log truck traffic.

Packer John Mountain is so big, rising to 7,100’ elevation, with many flanks and ridges, that the sheep had an abundance of feed on their way to Smith’s Ferry.

A Peruvian herder on horseback rides over the summit of Packer John with guard dogs and border collies in tow. Early snow hints at the coming fall.

Shipping Lambs – in Smith’s Ferry

On a sunny day in the end of August, Peterson’s herders brought the sheep down into a vast meadow next to the Payette River.

Sheep graze in a beautiful meadow in Smith’s Ferry.

The long hike from Avimor ends here. Tomorrow morning, the lambs will be loaded up on livestock trucks and shipped to a feedyard in California.

This has been a weird year for Peterson in a lot of ways with the Covid pandemic and other issues.

Prices are still bad. Peterson has no idea what kind of price he’s going to get for his lambs. He gets one paycheck a year at harvest time to cover a year’s worth of expenses, so it’s a huge deal.

“I was talking to my wife the other day. I don’t sleep very well, it’s a unique job in that you have only one paycheck,” Peterson says. “Probably a feeling like you might get gambling, you come to the corrals and then you go to the scales, it’s kind of suspenseful.”

While Peterson waits to see how much his lambs weigh on the truck scales tomorrow morning, his family and friends gather for an evening lamb feed and camp out on site.

Everyone wakes early at dawn to get ready to help load the lambs on the sheep trucks.

Everyone wakes early at dawn to get ready to help load the lambs on the sheep trucks.

They set up temporary corrals to hold the sheep overnight. They get the loading chute ready on the truck. Peterson’s son Penn separates the lambs from the ewes as they come down the chute, single-file. It all happens very quickly.

In a matter of a couple hours, the sheep trucks are loaded and head to the Horseshoe Bend truck scale to check on the weights. It turns out that Peterson’s lambs had a great year.

The lambs weighed an average of 128 pounds.

“That’s the best they’ve weighed … maybe the second best of all time,” Peterson says.

Three things need to come together to make a profit in the sheep business, Peterson says.

- A good lamb crop at lambing time.

- Good weights on the lambs at shipping time.

- A good price for lambs.

Peterson put his lambs on feed and waited for prices to improve. Fortunately, they did!

Every year is different, and even in a year with multiple curve balls, Peterson is upbeat. None of his herders got Covid; losses to predators were minimal, and they soldiered through all of the tough issues.

“I think it’s a wonderful way of life. I think it’s a wonderful industry,” he says.

Steve Stuebner is the writer and producer of Life on the Range, a public education project sponsored by the Idaho Rangeland Resources Commission.