My family has been in the ranching business for over a hundred years. I was born on a ranch and married a rancher that’s a lot like my Dad and takes care of cows all day, every day. One of our favorite things to do as a couple is to watch cattle graze.

But as peaceful as this scene looks, there’s a lot more going on here than you might think.

The relationship between grazing animals, and grass, is age-old and symbiotic. And it has the modern-day potential to address some of the most serious environmental threats we face today. The loss of species, floods and droughts, erosion of topsoil, recurring wildfires, even climate change.

But maybe you’ve heard that cows are a threat to the planet, and why would you listen to a rancher? Honestly, I come here less as a rancher, than as a crusader for my children, my children’s children, and the planet we leave to them. Because you see, it’s not that the cows are in trouble, the grass is in trouble.

Grass plays a vital role – it can be compared to the skin of the earth.

Grass is likely the least appreciated, but most abundant and important plant worldwide. Grass can be compared to the skin of the earth. For the human body, our skin is the first line of defense against disease. And what are these environmental challenges I’ve just described, if not diseases of our natural world?

Like our skin, grass keeps the planet hydrated and moderates temperature extremes for life in the soil. When our daughter was about 5, she’d just gotten out of the tub and I thought she was cold, but she said to me, “No Mom, I’m fine, I have my nice warm skin on!” Grass clothes and protects the planet.

Grass cover protects the soil from erosion, keeps the plants hydrated and protects watershed integrity.

A grass based landscape is critical to the water cycle. It acts like a sponge to catch rain drops, letting water seep down into the ground, instead of washing away and taking valuable topsoil with it. As it soaks in, it recharges springs, streams, and deep water aquifers. This “in-soak” is the hallmark of a healthy, functioning watershed. And we all live in a watershed.

Grass stops wind erosion, which you might think is old news, that happened back in the dust bowl years, but no, it’s a common worldwide problem still today. You can see evidence of it in our own community every spring.

And grass, through its vast root system, feeds life forms underground. A richly diverse and flourishing ecosystem below ground begets the same above ground.

Ruminants have a unique digestive system with 4 stomachs

So let’s go back to cows. Cows are a type of animal, plant eaters, called ruminants. Some of these ruminants are very familiar to us, deer and elk, sheep and goats, bison. And some not so familiar, reindeer, yak, water buffalo. They’re really unique in that they have a stomach with four compartments and a lengthy digestive process that includes regurgitating what they’ve swallowed to be chewed again. It’s called chewing their cud. They “ruminate.” Ever heard someone say they “need to ruminate” on an idea? Or they’ll say, “I need to chew on that?” Those phrases came from these animals. And it’s not surprising that they’ve influenced our language because many ruminants have been domesticated starting about 10,000 years ago and they’ve played a prominent role in the advancement of our own civilization.

One other bit of trivia is that most ruminants only have front teeth on the bottom of their mouth. On top is a tough leathery pad that they press their teeth against to tear grass. It’s an adaptation that makes them very efficient grazers.

Grass evolved to be eaten and thrives with periodic removal of old growth. What would your lawn look like if you never mowed it? Large ruminants also till the soil with their hooves and provide seed to soil contact that is needed for germination.

The grazing process has two very important outcomes: First of all, it converts much of the megatons of plants that grow every year, which are low in nutrients, high in fiber and hard to digest, into a highly-digestible, nutrient-dense food – meat – which is then available to omnivores like us and carnivores further up the food chain. Second, it recycles the nutrients and energy locked in those plants and returns them to the soil in the form of dung and urine to start the cycle again. In the soil are billions of microscopic decomposers that feed on one another, trade goods with roots, and build soil fertility. And they need recycled plant matter to feed the system.

So whether you choose to eat meat or not – that’s your decision – if you care about the planet, you should care about this cycle.

What I’ve just described to you, is a resilient landscape. Not just for cows and grass, but for all kinds of plants and animals and insects – flowering forbs for butterflies, brush for nesting songbirds. And it’s a landscape that is cycling carbon as it should.

Remember middle-school biology when we learned about photosynthesis? Plants pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and with the sun’s energy make food for the rest of us. It’s really that simple. It’s key to life on earth!

Photosynthesis and the carbon cycle.

Carbon, then, is held in plants until it’s released through respiration and decay ideally returning a net zero gain of carbon in the air. However, and this is the exciting part, if we can supercharge this system with deeper roots and more diversity – or better yet, reclaim barren dirt with cycling plant life, we can put more carbon into the soil where it belongs.

This cycle, the renewable, feedback loop of carbon. . . . Don’t confuse it with ancient carbon we extract for oil and gas. That is a one-way process generating a surplus of carbon in the atmosphere with no way to get it back in the ground.

As a rancher, you can imagine my reaction when I hear that eating more plants and less meat would address climate change. It ignores the fundamental difference in these two carbon systems. Let’s not take the ruminant out of the picture, when it’s one tool that can actually make a positive contribution.

There’s another facet of climate change that rarely makes the news. It’s a nasty word called desertification.

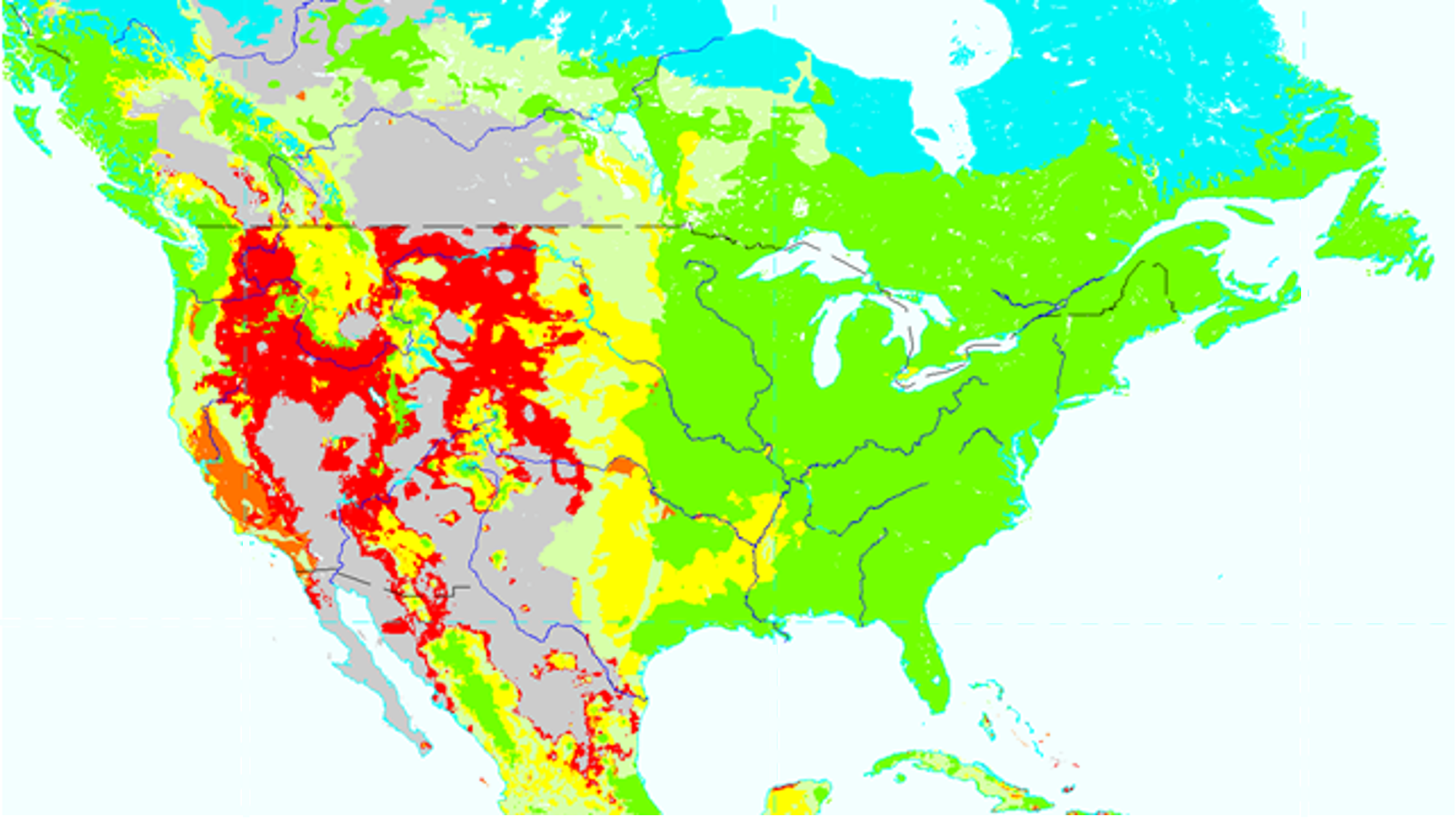

Red areas on map indicate “very high vulnerability” to desertification (Source: NRCS)

This map was produced by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. It’s called Global Desertification Vulnerability. Desertification means fertile land turning into desert. The gray areas are dry. The red areas are classified as “very high vulnerability.” Look at the West?

If land is turning into desert, it means the water cycle is deteriorating. There’s more barren ground and the landscape is losing that in-soak capability. When that happens, all life forms are at risk, even humans. The all-important carbon cycle is also deteriorating. Carbon that could be cycling is instead getting stuck in the atmosphere.

This map also highlights differences in climates. The Eastern U.S. is green because it’s humid all year long. In that environment, microscopic decomposers stay moist and active and plants cycle adequately. However, in the West where we have only seasonal humidity, decomposition of plants happens most readily in the gut of an animal, where it’s always moist, and always the right temperature. In the stomach of a cow live multitudes of the same types of microbes that live in the soil.

So the red areas are alarming. Here’s the deal. I agree with many experts – they just don’t make the news – that part of the reason this is happening is because we misunderstand the role that grazing animals play in the environment. Yes, on our continent sheep and cattle have been mismanaged in the past, left too long in one place, weakening the grass and exposing the soil. But in our ignorance, we’ve over-corrected by taking animals off the land, removing a vital link in the chain of ecosystem health, when what we needed was simply a better way to manage those animals.

It’s important to manage livestock grazing in a responsible way so it can have a positive impact on the earth and produce food and fiber for humans.

Luckily, this outdated way of thinking is slowly being reversed. There’s good news on so many fronts. In California, goats are nibbling brush to reduce fuels for wildfires and improve the soil at the same time. Cows are being managed in smart, environmentally friendly ways, leaving plenty of grass behind and waiting to come back until the grass is regrown. Farmers are putting livestock back into the cycle of crop production, which adds diversity and reduces the need for fertilizer. And in my world, conservationists are working with ranchers in ways, twenty years ago, we could only imagine.

All of this makes me really hopeful. But we need your help. You can assist these natural cycles too. When you mow your lawn, mow it tall, don’t mow it short! Let grass shade the soil. Grow a vegetable garden and do your own photosynthesizing. Put your phone away and take your kids outside.

We are not separate from nature, we are intricately dependent upon nature.

And please, keep learning with me. Have an open mind about animal agriculture and the environment. These animals are our allies, as they have been for thousands of years, and we just might need them now, more than ever.