BLM, Forest Service to follow new fire prevention strategy to preserve best sage grouse habitat in five Great Basin states, including Idaho

The Murphy complex wildfire, which burned about 600,000 acres of rangeland in southern Idaho and Nevada, is serving as a key catalyst in shaping western fire policy. In terms of size, the Murphy complex fire ranks among the top 5 in the nation in recent history.

After touring the Murphy fire zone recently, Interior Secretary Sally Jewell was inspired to develop a new fire-fighting strategy to prevent more large wildfires in the Great Basin.

“We went out on China Mountain and looked out over Browns Bench at some pretty incredible sagebrush habitat and looked out over the devastation of the Murphy fire,” Jewell said. “A picture is worth a thousand words. Being there is worth even more. You understand what’s at stake.”

Secretary Jewell’s visit to the Murphy Complex fire zone helped inspire the new fire preven-tion policy. Here she poses on Brown’s Bench with U.S. Senator Mike Crapo, R-Idaho.

Jewell wants to protect the best remaining sagebrush-steppe habitat for the greater sage grouse, a candidate for listing as an endangered species.

“Fire is the No. 1 threat to this ecosystem in the Great Basin states,” Jewell said at a recent press conference in Boise. “Gov. Otter and I and the western governors who are working on sage grouse conservation plans are really working on the preservation of the sagebrush steppe ecosystem. There are 350 species that depend on that habitat like mule deer, pronghorn, greater sage grouse, bald eagle, and many other species that call this home.”

Ranchers also want to preserve the native perennial grasses and shrubs in the Great Basin because healthy rangelands provide the best-quality forage for livestock grazing. Plus, public land grazing allotments are a crucial part of most ranching operations.

“We’re a patchwork outfit in that there’s private, there’s state, there’s BLM, there’s Forest Service. But it’s all key,” Rancher Mike Guerry explains. “You take one piece out of the puzzle and the operation doesn’t work.”

Jewell’s new wildfire prevention strategy, signed in Boise at a press conference with Gov. Butch Otter, makes stopping wildfires in the Great Basin the No. 1 national priority. The Secretarial Order affects five states and 42 million acres of private, state and public land.

Working with Rangeland Fire Protection Associations to speed up the initial attack on range-land fires is a key cornerstone of the new fire prevention strategy. Idaho leads that effort.

A cornerstone of Jewell’s strategy calls for working closely with ranchers as first responders via Rangeland Fire Protection Associations (RFPA’s) to give firefighters a better chance of stopping rangeland fires when they’re small.

The fire prevention strategy also includes:

- Creating fire breaks along existing dirt roads with dozer work and mowing vegetation.

- Pre-positioning firefighters and firefighting equipment close to core sage grouse habitat.

- Creating more RFPA’s in the Great Basin and providing more resources for them.

Idaho Governor Butch Otter applauded Secretary Jewell for beefing up RFPA’s for initial attack. “Now we have five organizations (close up stutter) representing 230 ranchers who live out on the resource and cover about 3.5 million acres,” Otter said.

Ranchers create the local RFPA organizations, the Idaho Department of Lands and BLM train them, provide firefighting clothing and communications, and they all work together when a wildfire occurs.

“It’s really, truly about the partnership with the BLM firefighters and the IDL firefighters,” Guerry says. “Classic example, two years ago, we had 21 starts, from Clover Creek to Richfield in a huge lightning storm. We were able to spread out with our people and BLM people, we held all of them to under 4,000 acres. Twenty-four hours later, we had a 60 mph wind, and all of the fires were out. That’s the proof of the pudding … it’s about catching the fires early.”

The big problem, Guerry and Jewell point out, is that because of drought and climate change, wildfires have been getting bigger and bigger every year. And they’re burning more frequently, too.

“When you come like I did out of the 1960s, we had 3,000-acre fires,” he says. “In the ’80s, we had 30,000-acre fires, to the 2000s when a small fire in the Jarbidge Resource Area is a couple hundred thousand acres and Murphy complex fires. There’s nothing mosaic or manageable about a 660,000-acre fire.”

“The reality is we have longer, hotter fire seasons than we ever have before,” Jewell adds.

In the BLM’s Jarbidge Resource area, for example, where Guerry runs cattle and sheep, repeated wildfires have burned up valuable sage-steppe habitat. Julie Hilty, a fire ecologist for the BLM, explains.

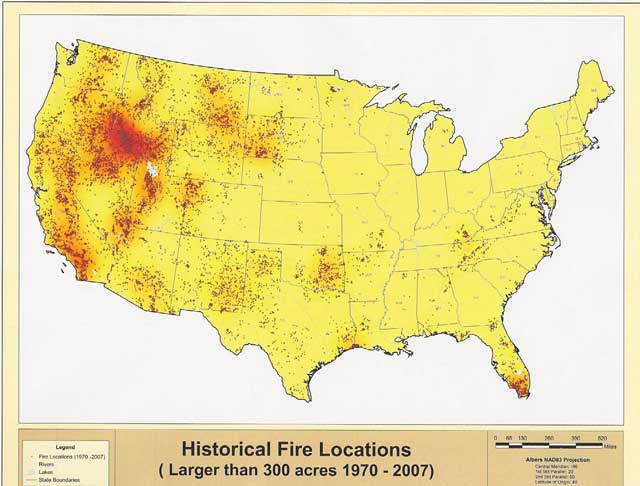

Southern Idaho and other parts of the Great Basin have had repeated, large wildfires as a result of climate change, drought and lightning storms.

“This map shows fire frequency in the Jarbidge field office over the last 15 years,” Hilty says. “This pink color shows areas that burned once. And, essentially, this very large area shows the extent of the Murphy complex fire that happened in 2007. Overlaid on that you see some darker colors that show other repeated fires. ”

Starting in 2005, we had several large fires. Clover fire burned about 170,000 acres. Sailor Cap burned about 100,000 acres in 2006. Murphy complex, over 600,000 acres in 2007. Longview fire which burned from this side of the field office to this side of the field office in 2010 was over 300,000 acres. And then the Kinyon fire burned from down here over to here in 2012. And that was over 200,000 acres.

So we’ve had this extensive, repeated fire cycle.

While the BLM does its best to restore the land following wildfires, it can take years for sagebrush and other shrubs to grow back. Plus, invasive species like cheatgrass and other exotic plants quickly take root after fires and out-compete native vegetation. That’s why sage grouse conservation plans list wildfire and the spread of invasive species as the No. 1 and No. 2 threats to sage grouse habitat.

“In my mind, fire prevention is a lot better investment than fighting fire and doing rehab,” says Mike Courtney, Twin Falls District Manager. “If we can catch them before they get big, strategize projects to keep fires small, we’ll be dollars ahead.”

A map of core sage grouse habitat in Idaho and the Great Basin shows that the stronghold of the bird populations are in areas where the native sage-steppe habitat still exists. These are the areas that Secretary Jewell wants to preserve with the new fire prevention strategy.

The BLM is gearing up for the first year of implementation in Idaho and four other states that comprise the Great Basin. “We’re pushing resources into those five states,” says Ron Dunton, Acting Assistant Director of Fire and Aviation at the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) for the BLM. “We’re buying extra dozers, buying extra water tenders, buying extra tractor-trailer rigs.”

The BLM will be pre-positioning firefighters and smokejumpers close to areas in the Great Basin as fire danger heats up during the summer months.

The BLM will be positioning smokejumpers, hot shot crews and incident commanders close to the Great Basin in the hot summer months. “I’m real confident in our ability to mobilize quickly and move quickly,” Dunton says.

The secretary’s strategy also calls for creating 9,000 miles of fuel breaks in the Great Basin. The fuel breaks are being created along existing dirt road corridors with blading and mowing.

Lance Okeson, Supervisory Fire Management Specialist for the BLM, takes us on a tour of fire breaks that have been bladed and mowed in Southwest Idaho.

“The fires that are getting away from us are going bigger and faster than ever before. So we need a fuel break system that’ll take that into effect,” Okeson says. “That’s why we need to go bigger.”

“In this fuel type, in the sagebrush, the fire can move through that in 8- to 14-foot flame lengths. Now that’s the reason to manipulate that sagebrush and mow it. So when the fire comes out of the sagebrush, and into the mowed strip, the flame lengths will drop down to a level where they’re easier to handle. That’s that break point, where we as firefighters can more safely engage.”

BLM contract crews are working on creating fire breaks in core sage grouse habitat areas throughout southern Idaho. Brandon Brown shows a 200-foot fire break along Grassy Hills Road in the Three Creek area.

“In the Murphy complex fire, this was all really tall sagebrush and the flame lengths were immense,” Brown says. “There was really no way to defend this area. It wasn’t safe. So now, when we have a wider road corridor, it’ll have a drastic effect on the flame lengths. It drops them down as the fire approaches the road, and the fire crew can do burnout operations safely and backfires without the flames jumping the road.”

Another key part of the Interior Secretary’s strategy is to stage firefighting equipment with RFPA’s in rural locations. Mike Guerry gives a rundown of the fire engines at his ranch in the Three Creek area.

“This is our commitment to the RFPA. We have many members who provide equipment, and this is what we provide,” Guerry says. “We provide two tractors and disks. They’re used right on the fire.

“This next piece is our water tender. This one will fill three engines. Carries 2,700 gallons of water. If we can get these staged close to the fire lines, the engines don’t have to come off the fire line for very long. And that’s key … to catching them quick.

“This is our fire engine. It holds 900 gallons of water. It’s all set up, we’ve got a fire pump and hoses on the other side. We’ve got 10 flat lines that we can run a 1/4 mile into if we have to. And then it holds all of our firefighting gear as well.”

Fire breaks allow the BLM to set backburns and stop wildfires from spreading on that flank.

Last, Guerry talks about his fire pickup. “This truck has been set up to fuel the tractors or graders. We’ve got a generator and air compressor along with the tools we need to service that piece of equipment so it’s ready for the next day. My gear is in it; when a fire starts I can jump in it and go. And it’s set up for communication as well.”

Looking at the Three Creek RFPA map, Guerry explains how the firefighting resources will be staged at strategic points throughout the 1.1-million-acre Three Creek RFPA during the fire season.

“This is where we’re located currently. Our first tractor and disk will be on Simplot’s private ground. My tractor and disk will be staged at the junction of the Clover Creek-Horse Creek Road. The second will be here at Coonskin Butte. Mike Henslee will have a tractor and disk on his private ground. And the remainder of the assets will be staged in the south end of the district.”

The third prong of Secretary Jewell’s strategy is to dramatically expand post-fire restoration activities in the Great Basin. Three types of restoration are planned:

- Planting grasses and sagebrush immediately following burns to restore plant communities.

- Converting old cheatgrass fields to diverse plant communities.

- Removing invading juniper trees from mountain meadow habitat to open up use of those areas for sage grouse.

“The scope of work that’s being identified is we need to do roughly 10 million acres of restoration, which is a huge magnitude of work for BLM,” Dunton notes. “One of the parts of the secretarial order is to start looking at large-scale treatment to turn back cheatgrass. A lot of people say that’s just too big. We can’t do that. We’ll never stop it. Well, if we don’t, we lose the whole basin. So we’ve got to figure out a way.”

Top photo: Pre-treatment photo of cheatgrass, burned sagebrush and nox-ious weeds in the Kimima area. Above: 10 years after treatment, perennial grasses and sagebrush are growing on the restored site.

At a recent conference, a participant suggested that post-fire restoration activities need to go beyond the fire boundaries, Dunton said. “One of the speakers, I believe it was someone from the Nature Conservancy, he said, “If we’re going to succeed, we need to start restoring 125% of what we lose to get ahead of the game. It’s not good enough to restore what we lose. We’ve got to do more than what we lose to reverse the trend.”

The speaker’s comments resonated with the BLM, Dunton said.

BLM officials recently showcased a project that converted 16,000 acres of cheatgrass and exotic weeds to perennial grasses and sagebrush, north of Burley. Brandon Brown explains. “This is the Kimama Restoration project. What we had here about 15 years ago was a monoculture of cheatgrass and annual invasive weeds. Through a series of treatments that took a couple of years, we were able to restore perennial grasses and sagebrush component on the landscape. What we did was a drill-seeding with the perennial grasses and an aerial seeding with the sagebrush. And this is the result we have 15 years later.”

The Kimama site is pretty dry, with only about 8-10 inches of precipitation per year. The elevation is 4,300 feet above sea level. The BLM started treating the site by burning off the cheatgrass and noxious weeds in the fall, Brown said. The following spring, they sprayed the site with herbicide to stop the spread of weeds, drill-seeded native and non-native perennial grasses on the site, and in the following winter, they aerially seeded sagebrush on the site. Today, it is looking much better.

“We built a lot of resiliency back into this landscape,” Brown says. “This is on a better ecological trajectory. We had a couple of goals with this project. One is to establish connectivity with habitat in Craters Monument. There’s really good habitat there, and we’ve been able to expand that.”

By getting rid of the cheatgrass, the perennial plant communities will be more resistant to fire, he explained. “By establishing this area, we’ve created a substantial fuel break, almost a landscape-level fuel break.”

Jim Sage Mountain pre-treatment (top) and post-treatment (above) in 2013. A masticator and chainsaw work were used to eliminate the juniper trees. Photos courtesy BLM.

Brown says projects like this could be done elsewhere in the Great Basin with good success. But they do take time to recover. “We plan on continuing to do projects like this so we can have an impact on the landscape,” he said.

The BLM Twin Falls District also recently worked on a juniper removal project to expand sage grouse habitat on Jim Sage Mountain. The project had support from the Sage Grouse Initiative and Idaho Fish and Game, among others, to improve habitat for the birds in mountain meadows.

“This is a juniper reduction project that started in the fall of 2013 and finished in the winter/spring of 2014,” said Dustin Smith, BLM Fire Ecologist for the Burley Field Office. “We treated around 5,000 acres. “As you can see from the hard line of juniper trees on the mountain, the junipers were encroaching from there to the area where we’re standing now. We used multiple methods — mastication and we used a lop and scatter method.”

Masticators are heavy equipment that grind up juniper trees into wood chips, and the lop and scatter method is done by chainsaw. “Shortly after we completed the mastication, some crew members were out here checking it out, and they spotted a number of sage grouse right in the mastication project,” Smith said, showing us a photograph.

The largest sage grouse lek in the Burley field office area is located about 1 mile away. The juniper removal project helped expand sage grouse habitat adjacent to existing habitat, BLM officials said.

Research shows that sage grouse won’t use areas with juniper trees growing on them, fearing that predators such as ravens will hide in the trees and prey on their young. Junipers also consume large amounts of water in meadow areas and sterilize the soil around them, making it very difficult for plants and forbs to grow there.

Sage grouse moved right into the juniper-treated area on Jim Sage Mountain, literally days after the BLM finished with the juniper-removal project.

After the junipers are removed, native plants and forbs bounce back quickly and sage grouse move back into the habitat. In early June, Indian paintbrush and other forbs were sprouting in the mountain meadow.

Both Secretary Jewell Sage grouse moved right into the juniper-treated area on Jim Sage Mountain, literally days after the BLM finished with the juniper-removal project. Below, forbs and grasses sprout after junper removal. and Gov. Otter are excited about the prospects for restoring public lands.

Forbs and grasses sprout after junper removal.

“The key to restoration activities is having consistent funding for it,” Jewell said. “The rehab is really important and the timeliness of the rehab is also important,” Otter said. “The only way to you’re going to beat that cheatgrass is to get other grasses growing there so the cheatgrass gets squeezed out.” Idaho ranchers are excited about Secretary Jewell’s strategy, too.

“I think it’s awesome,” said Wyatt Prescott, Executive Director of the Idaho Cattle Association. “It puts it on the map, makes it a priority, RFPA’s being recognized as a priority by the federal government. Everything we can do to help that agency and ranchers work together and get those first boots on the ground quicker is going to put us in a position of getting ahead of these fires.”

Jewell expressed gratitude to firefighters for trying to save the “sagebrush sea” in Idaho and the Great Basin. “Thanks everyone for the incredibly hard work you’re doing together recognizing the value that rangelands bring to this state, this region, and to the critters that don’t have a vote, because they’re important too, important to all of us, to our children’s future and our grandchildren’s future.”

Steve Stuebner is the writer and producer of Life on the Range, a public education project sponsored by the Idaho Rangeland Resource Commission.

© Idaho Rangeland Resources Commission, 2015