Jared Brackett – Ranching in a Fish Bowl

Jared Brackett raises black angus cattle in a very remote area known as the Antelope Springs Allotment, southwest of Twin Falls.

He grazes 600 cow-calf pairs on 50,000 acres of federal, state and private land in the allotment. You might say that Brackett ranches in a fish bowl because he manages his cattle alongside premium habitat for sage-grouse, a candidate species for listing under Endangered Species Act. The Bureau of Land Management is under court order to manage the area with tight controls to protect sage-grouse habitat.

Jared Brackett points out a sage-grouse exclosure in the Antelope Springs Allotment. The exclosure has grown from 1 to 5 acres with his cooperation.

But Brackett, the incoming president of the Idaho Cattle Association, doesn’t worry too much about that because Antelope Springs has plenty of feed and habitat for cattle and wildlife, he says. “This is as good as it gets. We’re quite proud of it. Unless you have something to hide, there’s nothing to be scared of. Because in the end, the resource will show what’s there,” Brackett says.

BLM officials say that Brackett takes excellent care of the Antelope Springs Allotment by following tightly controlled management guidelines, which allow for a maximum of 30 percent utilization of native grasslands in the allotment.

The Antelope Springs Allotment contains prime habitat for sage-grouse. So the BLM, which is under court order to protect the bird’s habitat, keeps a close watch on cattle use in the allotment. Photo by Ken Miracle

“On average, his grazing utilization is 20 percent or less,” says Ken Crane, supervisory range conservationist for the BLM in Twin Falls. “He’s well within what he’s required to meet, so we’re pretty comfortable.”

Brian Kelly, Idaho State Supervisor of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, complimented Brackett on his range stewardship. “The sustained efforts of Jared Brackett exemplify the land ethic, leadership and commitments necessary to ensure the long-term health of rangelands in the West,” Kelly said. “His efforts, and efforts by others like Jared, are essential to retaining species management at the local level, and illustrate that good business, good stewardship, and good conservation are not only compatible, but complementary.”

A group of sage-grouse decided to set up a lek next to one of Brackett’s cattle watering troughs, so he has discontinued the use of the watering area during sage-grouse lekking season.

“Jared is a great example of why the state’s cattle industry has been viable for over 100 years,” adds Wyatt Prescott, executive director of the Idaho Cattle Association. “We are faced with challenges everyday that, frankly, seem unsurpassable, and it’s progressive ranchers like Jared who continue to create new ways to operate in today’s environment.”

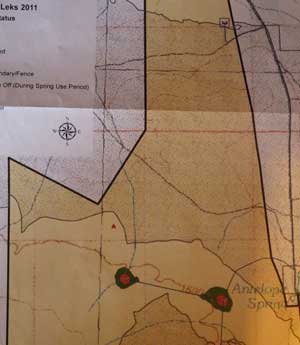

A color-coded BLM range utilization map, above, shows that Brackett’s cattle remained close to two water troughs in the lower portion of the map, while staying out of prime sage-grouse habitat in the top two-thirds of the map during lekking season. Cattle use of the sage-grouse habitat was 0-5%, according to the BLM, as shown by the tan color of the map.

Over the years, the Forest Service, BLM and Natural Resources Conservation Service have partnered with ranchers to develop about 50 miles of water pipelines in the Antelope Springs Allotment. The pipelines deliver water to many cattle troughs scattered throughout the allotment.

“It’s that group effort that makes it work,” Brackett says of the partnerships with the federal agencies.

The entire allotment is divided into 13 different pastures for year-round grazing — winter, spring, summer and fall. Fencing and agency regulations control where the cattle can graze during each season.

The water developments give Brackett and the BLM lots of flexibility. If they don’t want cattle to graze in a particular area, they turn the water source off, and push the livestock to another area with water and salt blocks.

In one instance, a group of sage-grouse set up a lek at a water trough area in a spring pasture, so Brackett shut off the water and left the sage-grouse alone to mate on the lek. “There’s been a water trough here since the 1970s,” he says. “I have four other water troughs in this field, so it’s not a big deal to turn this trough off during the lekking season. It makes it so the birds can lek without being disturbed.”

Crane points out another example of cattle and water management in a different sage-grouse lekking area.

“This red triangle here is an occupied lek,” he says, noting the lek on the allotment map. “So what we wanted to do was use water to manage the distribution of livestock. Jared turned the water off up here, and kept these two water sources on. We wanted to keep the majority of the use down here, away from the sage-grouse lek.”

The Bear Creek pond is fenced-off from cattle to protect water quality and wildlife habitat. Solar power provides the energy for water pumps to convey water via pipelines to cattle troughs.

And then the BLM followed up to monitor, map and document how the cattle used the area during sage-grouse mating season. Cattle use was 0-5 percent in the sage-grouse habitat area, shown in beige on the map, Crane said.

As Brackett takes us on a tour of the Antelope Springs Allotment, he points out that all of the water developments in the allotment have been fenced off to keep cattle out of riparian or wet meadows, leaving them available for sage-grouse and other wildlife. He and his neighboring ranchers have developed multiple water sources with pipelines to keep cattle on upland areas, where there is plenty of vegetation for feeding.

For example, Brackett visits a fenced-off pond at the head of Bear Creek. “This is exclusively for wildlife now,” he says. “It’s on private land, property owned by our neighbor Mike Gary. It’s one of three legs of the water system, and it’s a vital source. This is new solar technology. It takes less panels to run, the pumps are more efficient, and they’re better pumps.”

Brackett has another water source nearby where two types of alternative energy have been used to pump water — an old wind-mill at one time, and then a solar-powered pump. The solar system has older technology that requires a backup power supply and several large water-storage tanks. He may update to a newer solar system at some point to increase efficiency.

The Bear Creek pond “is a nice spot,” he says. “It provides not only clean water for our livestock, but also clean water for wildlife.”

Above, a sage-grouse male and female interact during the mating season in the spring. Photo by Ken Miracle.

Sage-grouse have been observed using the pond area in the summer and fall, when the females are raising their brood of young birds. “This would be a major water source for them. You can see the fine grasses around the edge, the bugs, major food source, when it gets drier, you’ll see a lot more birds in here.”

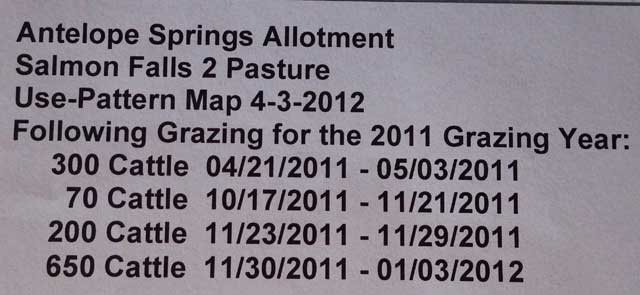

BLM sets forth how many cattle can graze certain pastures during specific time periods each year in the Antelope Springs Allotment.

In the top of the Antelope Springs Allotment, in an area known as the “beaver ponds,” Brackett developed a third water source that helps keep his cattle widely distributed in Browns Bench.

“This really opened up this top field for water,” he says. “It made a huge difference. It helps keep the cows out of the riparian areas, and the cows are happier, they don’t have to walk in here so far, and the water is cleaner. We’re pretty happy with this system.”

The project wasn’t easy to pull off, however, he notes, because of its remote location, and installing pipelines in rough-hewn country. “It took my brother, my sister and me about two weeks to put this system in,” he says. “We put it in in the late 1990s, right after I got back from college. It was a lot of work, and we were a lot skinnier back then, too. We had a D-8 cat, a road grader and a backhoe to get that system put in.

“There’s eight miles of pipeline and five water troughs in this system. It allows us to get the cows well-distributed in the upper fields. It’s probably one of the most important water developments that we’ve done up here.”

Brackett, who is a member of the Jarbidge Local Sage-Grouse Working Group, helped expand a large wet meadow exclosure to create more brood-reading habitat for sage-grouse. “About 10 years ago, we talked to the local sage-grouse working group, and they were looking for more wet meadow areas,” he says. “We thought it’d be a good idea to expand the exclosure. It used to cover an acre of ground. Now it’s close to five acres. We said you guys are welcome to have all of the wet meadow area, we’re not going to miss it. It’s good for the bird; we want you to use that.”

Water troughs in the Antelope Springs Allotment have bird ladders welded into the trough so any birds or small mammals can climb out if they fall in.

The BLM monitors and maps livestock use of the allotment throughout the year, Crane says. All of the pastures in the allotment have specific dates set for turnout, the number of cattle allowed, and how much forage can be consumed. The BLM has numerous monitoring points throughout the allotment where evaluate and measure upland plant utilization and sage-grouse habitat, and they have about 20 long-term study sites in the allotment. They check on these sites on a regular basis to make sure Brackett is meeting the specified conditions.

The water distribution plan is a big key to keeping the cattle distributed throughout the range, Crane says. “The water developments have really helped in dispersing cattle into the uplands, and you can see how the cows are grazing out here, that’s where we want them,” he says. “And Jared has done a real good job dispersing them into those sites, protecting the spring sources, the ponds, and riparian areas. Many of them are fenced off and are no longer accessible by livestock, so it reserves them for other uses particularly wildlife.

“And you’re protecting the water source, so you’re maintaining your water production, and you’re maintaining the quality water for cattle as well as wildlife, so it’s kind of an all-around win.”

“When people say we’re not doing anything for sage-grouse, we get a little bit offended because we spend a lot of time and effort working with them,” Brackett says. “We’re trying to do what’s right for everything. We’re worried about the antelope, the pygmy rabbits, spotted frogs, everything we have out here, it’s a total picture.

“We’ve been protecting and saving it for generations, and we’ll continue to,” he says. “Bottom line, the science isn’t going to lie to us. As long as the data is collected properly, processed properly, we’re in good shape. ”

Steve Stuebner is the writer and producer of Life on the Range, a public education project sponsored by the Idaho Rangeland Resource Commission.

© Idaho Rangeland Resources Commission, 2013