Following the reintroduction of 15 wolves into the Central Idaho wilderness in 1995, an additional 20 wolves were transplanted into Idaho from Canada. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service wanted to make sure they brought enough adult wolves into Central Idaho so they could pair up, set up territories and produce young on their own, restoring wolves to the Central Idaho ecosystem.

The experiment worked extremely well. The Central Idaho wolf population took off rapidly, just as transplanted wolves did in Yellowstone National Park. The Central Idaho wolf population grew quickly to the official recovery goal for Idaho – 10 breeding pairs or roughly 100+ wolves – in just three years.

Rocky Mountain gray wolves found rich habitat in Idaho with plenty of food, and their populations took off rapidly following reintroduction in 1995.

There was a record-high elk population in the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness at the time – an estimated 6,000 animals – so the wolves had plenty of eat.

“I didn’t expect them to take off quite like they did,” said Gary Power, who was the Salmon region supervisor of Idaho Department of Fish and Game at the time. “I figured they’d expand and do quite nicely because they had a food source, and they’d do well.”

Wolf advocates were overjoyed with having wolves setting up residence in Central Idaho. They went camping in “the Frank,” hoping to hear wolves howl in the woods at night.

Matt Miller and his wife went camping in Bear Valley, hoping they would hear wolves. Miller, lead science writer for The Nature Conservancy, has traveled to Africa and Brazil to see large predators.

“There were chinook salmon literally splashing in a stream by a campground, there were elk bugling up in the hills, and I thought what could make this better?” Miller says. “We climbed into our sleeping bags that night, and all of a sudden, my wife said, is that a siren? We had grown up around coyotes, it’s not a coyote, it’s wolves! For the next 45 minutes, there was this deep howling, echoing across the canyon, for me just being out there with those large predators, it makes the wild a bit more wild.”

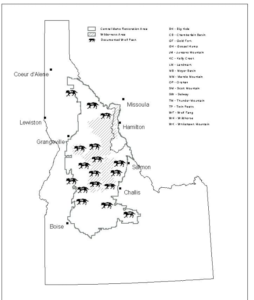

The original wolf recovery zones created by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

But it wouldn’t take long for wolves to prey on livestock. Just 9 days after the first batch of wolves were transplanted into Central Idaho in January 1995, Wolf B13 ventured 60 air miles to Salmon rancher Gene Hussey’s cattle pasture and was found dead from a gunshot wound, lying next to a dead calf that B13 had presumably killed.

The incident was an emotional flashpoint and made instant headlines in the regional and national media. Someone had shot and killed the wolf while it was feeding on the calf. Hussey notified the county sheriff and Wildlife Services immediately. A necropsy was performed in the field by a Wildlife Services agent.

“I find a dead calf, laying by wolf B-13,” says Layne Bangerter, who worked for USDA Wildlife Services at the time. “Perfect bullet hole in the chest of the wolf. Dead calf. I spent into the night, skinning the calf, everybody watching me making my determination. The calf had walked, it had been alive, and it was my determination that the wolf killed the calf.”

Ranchers were allowed to shoot a wolf caught in the midst of preying on their livestock, but a mysterious passer-by could have faced 1 year in prison and a $100,000 fine since the wolf was protected under the Endangered Species Act.

The wolf kill confirmed what ranchers had feared all along – that wolves would not necessarily stay inside the Frank Church or Selway-Bitterroot wilderness boundaries, and they would kill livestock on private ranchlands outside of the wilderness. This was the first of many incidents of wolves killing livestock to come.

Wolf B-13 strayed from the wilderness within days of its release, killing a calf at Gene Hussey’s Ranch on Iron Creek. B-13 was shot and killed next to the dead calf.

“The citizens of Salmon, Challis, were on edge,” Bangerter says. “The classic clash between the federal government and the state and local government was happening right in the wild west of Idaho.”

When it came to managing wolves in Idaho, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had to contract with the Nez Perce Tribe to do the field work and monitoring. The Idaho Legislature prohibited the Idaho Department of Fish and Game from assisting with wolf reintroduction in any way.

Knowing the political realities, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had bypassed the state of Idaho with the wolf-reintroduction program by releasing the animals on national forest lands controlled by the federal government. They didn’t need state permission, but if they had asked for it, they wouldn’t have gotten it. Idaho legislators didn’t take kindly to being forced to do anything by the federal government – especially something so controversial.

Former State Senator Laird Noh, chairman of the Senate Resources and Environment Committee, and a Kimberly sheep rancher, explains.

“They were obviously very opposed to it,” Noh says. “It just seemed somewhat insane, it didn’t make sense that you would bring a wolf back into the environment when you had worked so long for so many years over so many generations to eliminate that pain and suffering to your livestock.

State Senator Laird Noh, R-Kimberly

“So suddenly, here you’re in a situation, where you’re confronted with wolves, who are viewed as something that rips and tears and kills your sheep and livestock, and you’re prevented from protecting them as you would like to do.”

The gulf between urban environmentalists who wanted wolves in Idaho vs. rural ranchers, some of them state legislators, who opposed wolves, was as wide as the Grand Canyon. Big game hunters had mixed opinions. Some feared that wolves would decimate elk and bighorn sheep herds.

“It was the most controversial wildlife issue I was ever involved in,” Power says. “The emotions on both sides of the spectrum, from those who said they’re going to eat all the children, to those who said there’s never been a problem, and there’s not going to be any problems. It was just extremely tense.”

“You try to draw a good hand in life, but as someone once said very wisely, you’re much better off if you learn how to play a bad hand well,” Noh says. “That’s what Idaho had to do with the reintroduction of wolves under the Endangered Species Act. It was a bad hand. We had to use the law and do the best we could, which still wasn’t very good.”

USDA Wildlife Services, meanwhile, responded to wolf depredation incidents in Idaho, sometimes trapping and relocating wolves or taking lethal action to prevent further livestock kills. Wolf numbers continued to climb statewide.

The final environmental impact statement on wolf reintroduction predicted that wolves would kill about 10 cattle and 57 sheep per year when the population goal was reached of 10 breeding pairs in Idaho.

Idaho Wolf Pack map, 2001

Four years after wolf-reintroduction there were an estimated 140 wolves living in Idaho, 12 confirmed packs, with a minimum of 65 pups. Each pack had an average home range of 364 square miles or 233,000 acres of land.

That same year, in 1999, wolves killed 19 cattle and 64 sheep, affecting 14 different ranchers. Those were only the confirmed kills.

In hopes of reducing the economic blow to ranchers, Defenders of Wildlife, a national environmental group that pushed for wolf-reintroduction, set up a compensation fund to pay ranchers for the market value of livestock in the case of confirmed wolf kills.

By this time, it became clear to Senator Noh that state of Idaho needed to develop a wolf management plan that would be acceptable to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service so wolves could be de-listed from the Endangered Species Act and the state could manage wolves on its own. Idaho’s wolf population had already surpassed the benchmark for de-listing 3 years in a row.

The Idaho Legislature created a Wolf Oversight Committee that held multiple hearings around the state to develop a wolf management plan.

Meanwhile, wolf populations continued to thrive in Central Idaho. By the end of 2003, there were a minimum of 38 wolf packs producing litters in Central Idaho and 375+ wolves – more than three times as many breeding pairs as needed to de-list wolves in Idaho, according to the Nez Perce Tribe wolf monitoring report.

In the 2003 report, officials said the first benchmark for delisting wolves from the Endangered Species Act had been met. “Thirty breeding pairs across three restoration areas had been achieved by the end of 2002. The Fish and Wildlife Service anticipates the delisting process may begin in 2004.”

In 2002, the Idaho Legislature adopted a Wolf Management Plan for Idaho. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service accepted the plan. The Legislature was ready for Idaho Fish and Game to take over wolf management in Idaho.

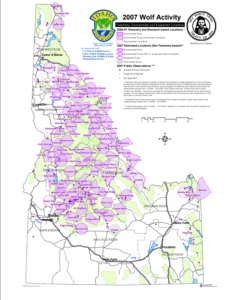

Idaho Wolf Pack map, 2007. Each purple circle indicates an active wolf pack. They were spreading far beyond the recovery zone in Central Idaho Wilderness at this point.

For wolves to be delisted from the Endangered Species Act one more benchmark had to be achieved – Montana and Wyoming also had to create a wolf management plan that was acceptable to the Fish and Wildlife Service. The state of Wyoming was slow in getting that done.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service tried multiple times to give Montana and Idaho a larger role in managing wolves under Section 10 (J) of the Endangered Species Act. But a number of national environmental groups sued the Interior Department to prevent the Service from doing so.

The judge ruled that he could not de-list just a portion of the recovering Rocky Mountain wolf population, without an acceptable management plan from the state of Wyoming.

By 2006, there were at least 673 wolves in Idaho and 76 wolf packs, according to an annual monitoring report by Idaho Fish and Game and the Nez Perce Tribe.

The same year, wolves killed 40 cattle, 237 sheep and four dogs in 117 different investigations on wolf-depredation.

The Legislature was getting an earful about wolves preying on livestock, and Idaho Fish and Game was hearing about wolves killing too many elk.

Former Governor C.L. “Butch” Otter, who was Idaho’s 1st District Congressman at the time, started to hold an annual trail ride to talk about land-management issues.

“We started the congressional rides in my first year as a congressman, and the idea was I wanted to bring some of those eastern congressmen, bring them in the Idaho, put them in the saddle, and sit around the campfire at night, and talk about these issues,” Otter said. “And in the first 4-5 years, it was wolves, wolves, wolves, wolves, and the continued growth in population.”

By this time, Layne Banger was working for Senator Mike Crapo as his top natural resources aide.

Gov. Otter led trail rides with government agency officials from Idaho and Washington D.C. starting in the mid-1990s to educate them about natural resources issues. “All we heard about was wolves, wolves, wolves,” Otter says.

“The frustration in Congress was, we’ve achieved recovery in Idaho, Yellowstone and Wyoming, and Montana, times 10, probably times 20, why isn’t the ESA working? Why can we not delist the wolves?”

In January 2007, the Fish and Wildlife Service published a rule in the Federal Register that de-listed wolves from the Endangered Species Act in Idaho and Montana. Both states had met and exceeded all the legal requirements.

In response, a coalition of 13 environmental and animal rights groups sued the Secretary of Interior, contending that it wasn’t appropriate to de-list wolves in only Idaho and Montana. They argued that Wyoming’s wolf management plan was too hostile toward wolves, and it would not be scientifically appropriate to de-list just a portion of the Rocky Mountain wolf population, among other things.

29,000+ wolf tags were sold in the first wolf hunting season in Idaho in 2009. (Courtesy Mystic Saddle Ranch)

Idaho Fish and Game held its first wolf hunting season in 2009. More than 29,000 wolf tags were sold, leading to a harvest of about 135 wolves. The wolf hunting season stopped the steady increase in wolf populations for the first time since wolf-reintroduction began. But wolves were much harder to hunt than anyone realized.

“The first year of the season, people couldn’t find wolves,” Power said. “And originally, they thought they were behind every bush in the state. So pretty soon, they got first-hand experience … they do travel a lot, they’re hard to find, and maybe there aren’t quite as many as what we thought there were.”

By the end of 2009, there were at least 835 wolves living in Idaho, including 94 wolf packs. Confirmed or probable livestock depredation incidents that year included 98 cattle, 442 sheep, and 15 dogs.

In 2010, a federal judge from Montana blocked de-listing and halted state management. No hunting or trapping would be allowed in 2010. But finally, in 2011, Congressman Mike Simpson of Idaho and Senator Jon Tester of Montana attached a rider to an appropriations bill, de-listing wolves from the Endangered Species Act in Montana and Idaho. The congressional maneuver was upheld in federal court.

Hunting and trapping seasons resumed in the fall of 2011 in Idaho. By then, the state’s wolf population was well over 850 animals – 101 packs in Idaho and 24 packs on the state border with Montana, Wyoming and the state of Washington.

Idaho wolf pack map, 2011

With state management in place now, Idaho Fish and Game could manage wolves as a big game animal with hunting and trapping seasons on an ongoing basis.

“Our goals are to manage wolves like bears and lions and deer and elk as part of the native wildlife resource,” says Jim Hayden, wolf and predator biologist for IDFG. “They’re here. They’re here to stay. Let’s manage them as a species in their own right. We’ve seen wolf populations do very well, expand, they’re very adaptable animal, they seem to be relatively stable right now.”

It had taken 16 years to get wolves removed from the Endangered Species List. Wolf advocates had succeeded in restoring wolves to Central Idaho in numbers far greater than the 10 breeding pairs that the reintroduction plan envisioned.

To ranchers who were concerned about the increasing incidence of wolf depredation on livestock, the reintroduction effort had strayed far off-course.

“We would have met the criteria for delisting in 1999,” says Casey Anderson, manager of the OX Ranch northwest of Council, Idaho. “Because of the pressure from the environmentalists and other groups, and the lawsuits, they just moved the goal posts down the field.”

Suzanne Stone with the Defenders of Wildlife says she was not surprised that wolf populations took off in Idaho.

“It’s not that surprising that they took hold, the way they did because they had such healthy habitat to support them,” says Stone. “It just made a perfect place to bring them back.”

Greater Northwest wolf pack map, 2012 … by this time, wolves were spreading into Washington and Oregon from Idaho …

With wolves delisted from the Endangered Species Act and the federal government taking over the compensation fund for livestock killed by wolves, Defenders ended its compensation fund in 2010 after paying out $1.4 million for confirmed kills.

By 2012, with wolves occupying most of Idaho north of I-84, the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and Western Montana, there were no longer any boundaries guiding wolf recovery in Idaho or the Northwest.

“That was the camel’s nose,” Otter says. “There was no way they, Babbitt, could possibly have believed that they would release wolves in a park in the Rocky Mountain West, and that’s where they’re going to stay.”

“They’re going to go out and establish new territories and they knew that. What were the unintended consequences? The unintended consequences were the fact that after the introduction, even with the denials, the populations of wolves exploded, the federal government had control of them, and they weren’t going to turn it over to the states.”

Next: Part 3 Meet Jay and Chyenne Smith: Raising livestock in Idaho