Striking a careful balance between grazing, wildlife, history and fishing at Harriman State Park

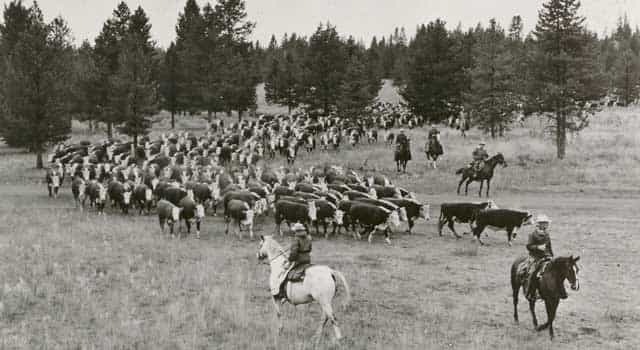

A big group of cowboys came together at the break of dawn on a Saturday morning to trail cattle about three miles into Harriman State Park.

Ranchers had gathered about 800 cattle the night before along Mesa Falls Road, a designated open range area. Two men on horseback led the drive. They had lots of riders on the flanks and pulling up the rear to keep the cattle moving in the right direction.

As they left the road and rode through the forest, the cowboys kept the cattle moving. On the highway, rancher Ron Wilcox and his daughter rode alongside the sheriff to get in position to stop the traffic.

Cowboys drive cattle along the Mesa Falls Road to U.S. 20 early on a Saturday morning near Island Park.

The cattle crossed the highway in the same spot where they have been driven into the park for decades. In a matter of minutes, the cattle moved into the park while the traffic was stopped on U.S. 20.

Rancher Ron Wilcox was pleased with the cattle drive. “It went really well,” Wilcox says. “We didn’t lose anybody or any cows.”

Their friends love to help. “A lot of them are friends, hey, can we help you when you do it. They want to get a piece of the old action. Live history a little,” Wilcox says.

Cattle have been grazing at Harriman State Park since long before the park was created in 1977. The Island Park Land & Cattle Company began grazing the park in the 1890s, when several men from the Oregon Short Line Railroad established the “Railroad Ranch.” In 1908, the ranch came up for sale. The owners approached E.H. Harriman in New York, chairman of Union Pacific Railroad, about buying it.

The cattle side of the Railroad Ranch operation was just as important to the Harrimans as the fishing and hunting. (Courtesy Harriman State Park)

“They approached him as it being one of the premier grazing spots in the area, there was waterfowl and great fishing, and things like that,” says Bert Mecham, assistant manager of Harriman State Park. “And E.H. Harriman bought it sight-unseen.”

Over time, prominent railroad and mining executives including E.H.’s two sons, Averell and Roland Harriman, Solomon Guggenheim and Charles Jones bought shares in the Railroad Ranch, allowing them to build cabins next to the prized “Millionaires Pool” on the Henrys Fork.

“It was a matter of love at first sight for all of us,” said Roland Harriman. “The glorious scenery and weather, the fishing, the hunting, the horseback riding and learning the lore of cattle handling all combined to lure us back there summer after summer.”

In the old days, cattle ranching and fishing co-existed without conflict. But in modern times, it’s a balancing act to keep anglers happy on the world-renowned Henrys Fork as it winds through Harriman State Park, while ranchers run cattle in the park’s vast, grassy pastures in the fall months.

Railroad royalty: E.H. Harriman, center, chairman of Union Pacific Railroad, with his two sons, Roland, left, and Averell.

“By and large, I think we co-exist pretty well here,” says Brandon Hoffner, executive director of the Henrys Fork Foundation. “Through the founders, we knew all along that grazing was going to be part of the management of Harriman State Park, and I think overall, the foundation has been supportive of that.”

“We appreciate having Harriman, in large part because of their corral system there,” says Shane Quinn Jacobson, a Rigby rancher. “We’re not alone. There’s half a dozen ranchers graze in the forest around the park, and then come into park in the fall, and use the corral system to sort and load and get back down off the mountain.”

Harriman State Park keeps the history alive with an annual Heritage Days event. The barns at the park have been carefully preserved to showcase the history of work horses, sheep and cattle. (Courtesy Harriman State Park)

The Railroad Ranch has a deep history that shapes what Harriman State Park is today. Unlike many state parks, there is no camping allowed. The park’s main mission is to provide a refuge for waterfowl and wildlife, showcase the ranch’s history, offer summer and winter recreation trails and seasonal livestock grazing. They also rent cabins and yurts to the public.

A few miles from the main park, visitors can tour Upper and Lower Mesa Falls, spectacular water falls on the Henrys Fork. The Upper Falls, the tallest of the two, plunges 115 feet before it flows downstream through pine and fir trees in the Caribou Targhee National Forest.

Rocky Mountain elk were released on the Railroad Ranch in the early days to help build an elk herd in the Island Park area. (Idaho State Historical Society)

Park staffers frequently give historical tours of the ranch buildings and barns at the park. Each building contains interpretive information about its historical use and occupants. The Jones cabin provides hints of the hunting and fishing lifestyle with big game trophies on the wall and capes on the floor.

The horse, cow and sheep barns all contain some of the original tack and equipment. Cattle, sheep and even elk were raised at the ranch in the early days.

“One of the pastures out here is called the elk pasture,” Mecham says, while giving us a tour. “They had quite a few head of elk and they released them into the Island Park area to help create the elk herd up here.”

Cattle were loaded onto trains in Island Park to ship them to the market in the fall. (Courtesy Harriman State Park)

A lot of the early farm implements are still on display. Harriman Park hosts a special event called Heritage Days each year for school kids and park visitors to learn about early farming techniques. “And of course they had horses to work the land and harvest hay, and things like that,” Mecham says. About 1,000 cattle grazed on the home ranch and in the nearby forest.

The meadows were irrigated as well. When it came time for the fall cattle roundup at the Railroad Ranch, everyone participated. They rounded up the cattle by horseback, sorted them in the corrals and then shipped them by rail car to the market.

The same corral system is used to sort cattle today. “There are relatively good facilities in the park to sort and load out of. It’s good all the way around,” says rancher Ron Wilcox.

The Harrimans and Charles Jones also were avid fishermen. Their fishing waders are still hanging in their cabins. Nowadays, the Henrys Fork is a super popular fly fishing stream. Brandon Hoffner tells us why.

“We’re approaching Harriman Park headquarters,” Hoffner says, while rowing a drift boat through the placid waters. “This stretch of river of course is world-renowned for its hatches, loved by dry fly aficionados, also known as the place where you come to get your Ph.D. in fly fishing. Really challenging to hook a fish here, but also a challenge to land it.”

The Harrimans’ riding chaps and fishing waders are still there, hanging from a hook in their beloved cabins on the banks of the Henrys Fork.

The Harriman family inspired the creation of the whole Idaho State Park system when they offered to donate the 16,000-acre Railroad Ranch to the state of Idaho. The terms of the Harriman donation required that it be managed by park service professionals. That meant Idaho would need a parks system.

They drew up the agreement in 1961, but the Idaho Legislature didn’t create a state park system until 1965. The park was officially conveyed to the state of Idaho in 1977. It opened to the public in 1982. The gift deed made it permissible to allow cattle grazing and fly fishing in the park. By the mid-1980s, however, it became evident that fencing off the Henrys Fork to cattle would be essential to keep the peace between anglers and ranchers.

Former Idaho State Parks Director Steve Bly looks over the park plans with Roland and Gladys Harriman in the 1970s. The Harrimans inspired the creation of Idaho’s state parks sytstem with their 16,000-acre gift of the Railroad Ranch to the state of Idaho.

“There was bank degradation, and we had issues with cattle in the river, and tense feelings between the people running cattle and the anglers utilizing Harriman State Park,” Hoffner says.

As a solution, a lay-down barbed-wire fence was built for eight miles along the west side of the Henrys Fork, and a solar hot-wire fence was put up on the east side. The fencing projects were one of the largest of their kind at the time. Ranchers and the Henrys Fork Foundation are responsible for maintaining certain sections of the fences. Park officials no longer maintain the fences.

“The riparian fencing was one of the cornerstone projects of the Henrys Fork Foundation,” Hoffner notes. “Even 30 years later, it’s still something that our organization focuses on, knows about, they understand that history. “It’s almost funny in a way that they’ll see a couple of cows in the river, they’ll call us immediately. Even though there’s just a couple of cows in the river is not a big deal, they get out, it’s nothing like we had before. It would never cause the kind of damage they had before. It’s still an issue that our membership pays close attention to.”

The ranchers are used to getting calls about the fences being down as well. The problem is sometimes caused by elk tearing down the fence before cattle are even in the park, sometimes weeks before cattle are grazing in the park.

“The park has been calling me pretty regular in the last month,” Wilcox says. “The fence was down here, and there, I told them we weren’t coming on till the 10th, and they were, you need to hurry and get it up.”

Adds Jacobson, “I just went in there yesterday, we put up a fence 4 days ago, the elk had it 1/2 miles’s worth, where it’s just a little electric fence, it doesn’t take much, they had it knocked down pretty bad … I had to go put it back up yesterday, and they may have it knocked down again already.”

Fence maintenance is an ongoing issue to keep everyone happy. “We’re doing our best to keep cows off the river,” Mecham says.

Volunteers with the Henrys Fork Foundation install fence posts for the first riparian fence along seven miles of the Henrys Fork, a blue-ribbon trout stream, to keep cattle out of the river and prevent damage to the streambank. This project occurred in 1986. Fencing helps keep the peace between anglers and ranchers. (Henrys Fork Foundation photo)

Harriman has three areas where it allows livestock grazing, Bert Mecham explains while showing us a big-picture map. Grazing is allowed on the Harriman East unit for three months, with a maximum of 400 AUM’s or animal unit months. In the ranch section, 1,600 AUM’s are allowed from mid-September to mid-November. The largest grazing unit in the park is the Sheridan unit, near Island Park Reservoir, with 4,600 AUM’s.

“It’s a really big pasture, it’s all pasture, and it’s all irrigated, so it’s pretty valuable, and it’s coming up for renewal. This month we’re having an auction for it,” Mecham says. Grazing fees have been going up at Harriman Park in recent years to help increase income for the park. The budget for Idaho State Parks got slashed during the recession, so the pressure is on for park managers to increase revenue.

Anglers come from all over the world to fish for big rainbows in the Henrys Fork.

In the last two years, Harriman Park has held sealed-bid auctions and oral auctions for grazing opportunities, and the bid prices have been soaring to heights never seen before.

Ranchers Ron Wilcox and Shane Jacobson are paying $27 per AUM in the ranch section of the park through sealed bids. But they were amazed to see an oral auction for the Harriman East unit go to $45 per AUM last year.

“In order to keep the lease, we’re paying through the nose for it, but not as much as this other lease that came up in the last few months,” Wilcox says.

“Well, there’s competition for grass right now,” Jacobson adds. “And one challenge we had when our permit expired, it’s a bid system, park wanted to do a closed bid, forced us to pay private land lease prices for fear of losing the corral system. As a group, we had a big meeting, and decided we better bid high, so we can keep it.”

The ranchers are working with higher levels of state government to look at the grazing fees charged at the park and find something that’s sustainable over the long haul. They want to keep grazing in the park.

The corrals at Harriman State Park are just as valuable as the grazing areas in the park so ranchers can sort cattle prior to leaving the park in late fall. (Courtesy Harriman State Park)

Harriman Park officials say they want to continue to allow grazing in the park as well. The leases are set up to last for five years, with an option to renew for another five years. “If they didn’t like the rate of the lease, we could terminate it and go out for bid again. Or if the park doesn’t like the way things are going, it gives either party an out,” Mecham says.

“I fully believe that if we work together, manage our resources not only can we provide feed for the public, also can improve the range for wildlife,” Wilcox says. “It’s got to be a win-win situation or one of us will lose obviously. That’s the key is sustainable.”

“We try to be as supportive of agriculture, both farming and ranching, as we can be,” says Hoffner. “We live in this community, we’re supportive of the people who live here and work here, our neighbors, and we’re looking for solutions to work out these issues so we can have a win-win in the end.”

Steve Stuebner is the writer and producer of Life on the Range, an educational project sponsored by the Idaho Rangeland Resource Commission.

© Idaho Rangeland Resource Commission, 2016