There comes a point, where enough is enough.

That’s how Curtis Elke felt, thinking about the gigantic swaths of cheatgrass that have overtaken the Southern Idaho landscape, and the huge range fires that can follow.

Curtis Elke, NRCS State Conservationist

“Something needs to be done! Basically, we’re at war with cheatgrass right now in the state.”

As the Idaho State Director of the Natural Resources Conservation Service, Elke is providing leadership and funding for a new multi-agency program called the “Cheatgrass Challenge.”

The project has strong support. NRCS officials are partnering with more than 10 state and federal agencies, ranchers and conservation groups to take an “All Hands, All Lands” approach to combating cheatgrass.

The strategy is to defend lands where native grasses, forbs and shrubs dominate the landscape, and cheatgrass and other noxious weeds are just beginning to invade pockets of land, here and there.

“The quote we used is, “Defend the core, Grow the core,” Elke says. “We’re not throwing our resources into heavily infested areas, but we’re looking at areas that actually have a chance.”

Adds Josh Uriarte, project manager and sage grouse coordinator for the Idaho Governor’s Office of Species Conservation, “We’re moving forward and defending the best of the best places that are starting to be invaded, and we’re expanding that and defending that core to make sure it doesn’t get overrun.”

At the ground level, they’re defending the core by spraying pockets of cheatgrass with herbicide via helicopters and ground crews. Treatments are starting in core native habitat areas in Eastern Idaho – from North Fork near Salmon to Birch Creek, north of Mud Lake.

“I think the program is going well. We’re just getting started,” Uriarte says.

What is Cheatgrass? Why is it so bad?

Cheatgrass can take over rangelands, especially following wildfires or repeated wildfires in the same location.

Cheatgrass, also known as Downy Brome or by its Latin name, Bromus Tectorum, is native to Eurasia. It was accidentally brought into the United States beginning in the 1880s via ship ballast, contaminated crop seed, packing material and other means.

Once introduced to the U.S., cheatgrass quickly spread into the Great Basin of the West. By 1980, cheatgrass had spread to every county in Idaho, Montana and Wyoming. It’s an opportunistic annual plant that greens up earlier than native plants and outcompetes perennial grasses and forbs following wildfires and ground disturbance.

Known as a winter annual, cheatgrass starts growing in the late fall, grows roots in the winter, and grows fast in early spring, just as native plants are beginning to wake up.

That timing allows cheatgrass to out-compete native plants and grasses.

“So it’s going to get ahead of the whole system and change the whole ecosystem,” said Wade McPhetridge, fire management officer for the Salmon-Challis National Forest.

Cheatgrass seed heads become highly flammable after the plants dry up in the summer.

Cheatgrass plant can grow to a height of 10-20 inches in the spring, when it’s palatable to wildlife and livestock. Each plant produces multiple seed heads with 25-plus seeds per plant.

By June or July, cheatgrass turns brown and dies. Then, it becomes a serious fire hazard on rangelands for the rest of the hot summer season.

“It’s a grass fuel model, right? All this stuff down here really low, you put a match on it, when dry and get wind, it could run to the top of the hill, within an hour or less,” McPhetridge says.

Cheatgrass has been compared to “tissue paper” in terms of how flammable it is on rangelands. The size of range fires in Idaho and the Great Basin has grown exponentially in recent decades because of cheatgrass invading native rangelands.

But by preventing cheatgrass from overtaking good native range, officials hope to reduce the threat of wildfires. “Yep, that’s why we’re spraying in the fall,” McPhetridge says.

Herbicide treatments near Salmon

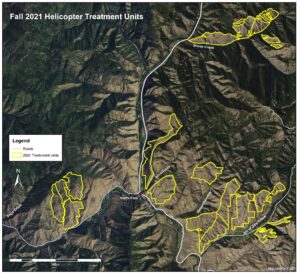

Helicopter flies herbicide on rangelands adjacent to U.S. 93 between North Fork and Salmon in Fall 2021.In Fall 2021, Salmon-Challis National Forest officials oversaw aerial herbicide spraying on about 7,500 acres of land that had pockets of cheatgrass.

A Forest Service map shows the areas where the herbicides Milestone and Plateau were applied.

Yellow polygons shows patches of rangelands that were treated to kill cheatgrass.

The herbicides target cheatgrass and other annual weeds, but it does not harm native plants, officials said.

“So far, we’re finding it’s highly effective,” says Diane Schuldt. “And the other thing it also does, it will control some of the herbaceous weeds such as spotted knapweed, which is a really big problem around here, and rush skeletonweed. So we’ve really been happy.”

Will the herbicides really kill all the cheatgrass?

“Amazingly yes. Our contract specs for helicopter operations are for 95 percent control,” she said.

The BLM has similar objectives. It’s treating about 2,500 acres of land nearby with a professional ground crew, WMA Specialists, based in Bonner, Montana.

“It’s classic program management where you start with an herbicide regimen, if you need to augment with native seed, you do such, then post-treatment we want the natives to succeed,” says Charles Morton, Range Technician for the Bureau of Land Management, Salmon Field Office. “We don’t want to become dependent on herbicides, we want to use them as a tool and then let the land stand on its own.”

Ricky Grant, right, leads the WMA Specialists spray crew across a mountainside on BLM land in Carmen Creek.

Ricky Grant, crew leader for WMA Specialists, says his crew takes pride in holding the line on cheatgrass.

“The cool thing is spraying that area where it stops and preventing it from going higher and spreading. Personally, for me, that’s where I find gratitude in it. Working in these remote areas where you can actually see a difference and make a difference,” Grant says.

A dye in the herbicide mix makes it easy to see the treated area.

The WMA Specialists crew maps the terrain they’ve treated while they work for future reference.

“You feel good about it too because you’re getting some exercise,” he says. “We’re out here to work, right? Sun up to sundown. On bigger days, we’re talking 5,000-6,000 feet in a day, that’s pretty common.”

USFS test plot post-treatment. Cheatgrass is gone, and native grasses have room to grow. (Courtesy USFS)

In the planning stages, Schuldt and other Salmon-Challis National Forest officials experimented with test plots to see how the herbicides affected cheatgrass survival and how native plants responded following treatment.

“Because we weren’t convinced ourselves,” Schuldt says. “So we did things small, less than a 1,000 acres. We didn’t know what we were going to see. And we were pretty blown away. Yeah.”

“We spray in Oct or Nov, and by the following April, May, June, we’re seeing the native response,” she says. “Native annual forbs, we wouldn’t even think they’re present anymore, the viable seeds are still present in the soil, just waiting for times to get better, and the minute they didn’t need to compete with the cheatgrass, the viable seeds are coming up and blooming the following year, it’s pretty amazing.”

In the spirit of the “All Hands, All Lands” approach to the Cheatgrass Challenge, the Mule Deer Foundation treated 1,423 acres of cheatgrass on private lands in five drainages near Salmon, including Carmen Creek.

Native core habitat thrives following treatment. (Courtesy USFS)

Carmen Creek Rancher Seth McFarland welcomes the control effort.

“Carmen Creek has always been a hot spot for weeds, and it’s also critical winter range for mule deer and elk here. Even though there’s little pockets (of cheatgrass), it’s extremely important to treat,” McFarland says.

The Mule Deer Foundation also is working on improving winter range for deer and elk. An estimated 10,000 mule deer and 8,000 elk depend on native grasses and shrubs in winter range areas in the Lemhi and Beaverhead mountains.

Farther south, the BLM contracted with WMA Specialists to do ground-based cheatgrass control work on about 50 acres of public land in the Birch Creek area.

All of the cheatgrass and weed control work in the greater Salmon area and Birch Creek blends several federally funded initiatives from the Forest Service, BLM and NRCS together for the greater good. The BLM projects were funded as part of the Cheatgrass Challenge. Herbicide treatments accomplished by the Salmon-Challis National Forest are part of an NRCS/USFS Joint Chiefs’ Initiative, where the agencies are targeting cheatgrass and other annual invasive weeds as fine fuel components.

“This work ties in very nicely with our Cheatgrass Challenge dollars as our priority area for Cheatgrass Challenge partially overlaps with our Joint Chiefs priority area,” said Rosana Rieth, NRCS District Conservationist in Lemhi County.

Federal projects also dovetail with local projects led by NRCS and other local entities such as the Lemhi Soil and Water Conservation District with participating private landowners.

Carmen Creek rancher Seth McFarland

Seth McFarland is one of the participating landowners. “What’s so cool is that we don’t have the manpower to go out and treat all of these places. We can treat these little isolated places, but with this approach, we’re getting something done,” he says. “There’s no doubt there’s going to be a huge difference, impact from this wide scale of control.”

Computer Mapping helps target cheatgrass infestations in Core areas

To identify areas for treatment, the Cheatgrass Challenge team is using several high-tech satellite mapping platforms.

“When we come to projects like this Cheatgrass Challenge, we’re working on a landscape scale,” explains Charles Sandford, a wildlife biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and BLM. “It can be really difficult to understand the state of the landscape. So when we have remote-sensing technology, we’re able to quickly see a huge picture of what we’re dealing with, where our potential areas of concern area, and where we can probably get the best bang for the buck.”

“With the Rangelands Analysis platform, which is Rangelands.app, freely available to anybody, we can pull up any data that we think would be relevant to this project – landscape scale, annual grass cover, perennial grass cover, tree cover, shrub cover, and we can see where annual grasses might be high, why that might be, and we can compare it to actual boots-on-the-ground data we have.”

The Rangelands Analysis platform is a combination of satellite data and aerial imagery. The Cheatgrass Challenge team also uses aerial imagery from Open Range consulting in Utah, which has developed high-resolution ground-level imagery for natural resource analysis.

Being able to use both platforms is a big plus, Sandford says.

Forbs sprout amid native grasses post-treatment. (courtesy USFS)

“By being able to take a snapshot in time in one year, and have a pretty reliable estimate of the status of 40,000 acres, we can say we’re comfortable with saying, here’s 5,000 acres that needs to be treated, and needs to be treated soon,” he says.

Aerial imagery from those computer platforms also will be able to show the progress of Cheatgrass Challenge treatments over time.

“We know since the ‘90s, we’ve had an increase in annual grasses. So in the 2020s, we are getting aggressive on annual grasses and in 2030s, we can push play, and hopefully see the peak in the 20s and back down in the 30s, if we’re successful,” he says.

Still, while the herbicide is supposed to be effective in suppressing cheatgrass for several years, cheatgrass seeds can be viable for up to 7 years.

So they’ll need to monitor the treated areas and do any additional herbicide treatments as necessary, officials said.

Beyond the areas treated in the greater Salmon and Birch Creek areas, the Cheatgrass Challenge team has started treating cheatgrass and invasive annuals in a number of other locations:

Beyond the areas treated in the greater Salmon and Birch Creek areas in 2021, the Cheatgrass Challenge team has been treating cheatgrass and invasive annuals in the following locations:

- Cottonwood Basin – completed herbicide treatment on 358 acres.

- Grassy Ridge/Sand Creek – completed 143 acres of fuel break.

- Crooked Creek/Lower Birch – completed phase 1 treatment of 2,200 acres with herbicide treatment.

- Upper Birch – Approximately 134 acres of annual grasses were treated with herbicide. More treatments are planned.

Six more areas are proposed for treatment in 2022 to defend “core” habitat areas:

- Upper and Lower Birch Creek, expanding upon what’s been treated so far.

- More treatments in the Sand Creek/Grassy Ridge area in Clark/Fremont counties.

- Reynolds Creek area in the Owyhee Mountains.

- Uplands areas in the uplands around Hailey and Bellevue in the Ketchum Ranger District.

- East Fork Salmon River area.

“If it works out, we can see our core actually growing,” Uriarte says. “So I think that’s where we’re heading long-term. As we strategically place these projects, and more people buy in around them, we’ll grow those core areas outward.”

“We feel really fortunate to be involved in it,” McFarland says. “Federal partners have been outstanding for us here in the valley, and being able to come together and not just taking our private and treating it alone, but to be able to go out and extend beyond the boundaries – that all hands, all lands approach … feel like we’re making a difference on the ground.”

“This is not going to be a one and done, or a one or two-year kind of solution,” Elke says. “I really feel confident that we have the partners, we have the interest, we have the energy, we have the intelligence, and the formulas for success from bringing where it is today to down the road for many, many years to come here.”

Steve Stuebner is the writer and producer of Life on the Range, a public education project sponsored by the Idaho Rangelands Resources Commission.